Light Up a Candle

Brother Chân Pháp Ấn

Arriving at Plum Village

Dear Brother, could you please share with us your early experiences in Plum Village?

In July 1991, I wrote a letter to Thay asking to become a monk. At the time, I was working at the research institute of a petroleum company called ACCO. Only after I finished writing the letter did I then inform my group of close friends. One after another, they took turns to call me, trying to persuade me not to ordain. They told me that it would be such a waste if I became a monk. My more than 28 years of study would be of no use if I did not serve society, contributing the knowledge I had gained. If my current work environment was not so nourishing for me, I could always go back to teaching at universities. I am someone who usually listens to advice from friends. After reflecting on it some more, I decided not to send the letter to Thay.

I then started working at MIT as a teaching assistant while continuing my own research. But after working there for a while, I still could not find much inspiration. By the New Year’s Day of 1992, I felt strongly that I must become a monk! I sent Thay the letter I had written in July, 1991. Then Thay asked Sister Chan Khong to call me. After enquiring about my background and my wish to become a monastic, she said, “Plum Village is in a muddy place, in the middle of nowhere. Life is very tough here. Can you bear it? You have a career now. If you are ordained, you have to give it all up. Can you accept that?” I replied, “I am ordaining just to ordain. No matter the conditions, I will not change my mind.” Sr. Chan Khong said, “If so, you should make arrangements to come here immediately.” On the eve of March 26, I left the U.S. for Plum Village.

Brother Hoang (who later became Br. Phap Lu) picked me up in a blue van. There were not many vans at that time in Plum Village and they were all old. That blue van was still in use more than ten years later. The afternoon of March 31, I set foot for the first time in Lower Hamlet. Thay was waiting there to have lunch with me and after that, brought me to Upper Hamlet. It was a very beautiful memory.

In Upper Hamlet, Thay asked the brothers if they had prepared a room for me. The brothers said yes. Then Thay walked me to my room. “Prepared” meant a room with a bed made of a piece of plywood on four bricks–nothing else. At that time, anyone who came to Plum Village brought with them a sleeping bag. Sr. Chan Khong also advised me to bring one of my own. I stayed in one of the two rooms in the Bamboo Building, now the bookshop in Upper Hamlet. The walls were made of stones stacked on top of each other and were plastered with clay. Because of age, the clay was cracked in many places. Sleeping at night, I could feel the wind on my cheeks and sometimes, even my hair froze if it got too cold. Plum Village was like that then. The facilities were very basic and scant.

Despite the difficult living environment, I always kept my aspiration. I made the vow that no matter how challenging the circumstances were–even if I had to beg for food, to be homeless, I would keep going in order to understand what true enlightenment is, what liberation is.

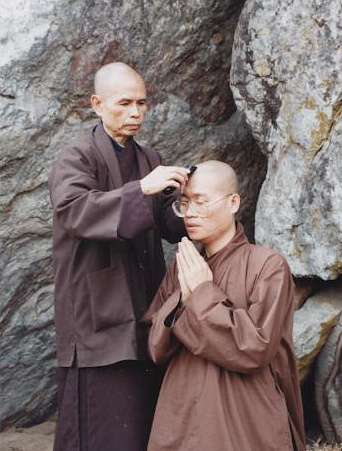

The predestined relationship between teacher and disciple

Why did you choose Thay as your teacher?

I had heard of Thay since I was young. On my older sister’s birthday in 1967 or ‘68, my father gave her the book A Rose For Your Pocket as a gift. But at that time I was too young, maybe only six or seven years old. I read the book but I did not understand it at all. Later, in the first few years after moving to the U.S., I read it. Then in 1983, when my father came to the U.S., one of his friends sent him the book The Miracle of Mindfulness. I read it and began to practice. I remember practicing walking meditation from one building to another on my university campus, counting the steps, just as Thay taught in the book. I tried to follow exactly the guidelines given in the book, but I forced my breathing so much that I was exhausted and almost could not breathe.

In the autumn of 1985 while I was studying in California, Thay came to the U.S. for a retreat in Austin. My whole family joined that retreat. My parents dearly love and respect Thay. Then in 1988, I joined another retreat in Southern California. That was the year Sr. Chan Khong ordained on Vulture Peak.

From when I was a high-school student until I became a monk, I had read many books and listened to many teachings about meditation from different Zen masters. But only when I encountered Thay’s book Vấn đề nhận thức trong Duy thức học (Consciousness in the Manifestation Only School) that I intuitively knew–here was my teacher! The more I practiced, the more I felt that the conditions that allowed me to meet Thay had been sown many lifetimes ago.

In the past, I thought that I was choosing this teacher or that teacher, that I liked this temple or that temple. But in the end, all phenomena come together due to conditions. The first few days in Upper Hamlet, I often dreamt about Thay practicing sitting meditation. He sat very straight and in a regal way. I could feel that the connection between us went very deep. I have many memories with Thay that really nourish me.

I remember during my first days at Plum Village, I asked many questions. At first, Thay was happy when I posed questions. However, after he saw that it was a habit of mine, he stopped giving me answers and left me to practice. That was very wonderful. I came here with all kinds of questions that no one could give me a final answer to. What I needed to do was to practice, and with time, the answers would come by themselves.

The work of sangha building

You were present during the very early years of Plum Village, witnessing the changes and growth of the sangha. Was the journey of sangha building tough? Have you ever felt exhausted? What helped you to continue preserving and growing the sangha?

I recall in Thay’s Dharma talk before the ordination of the “Fish” family in 1993, he said true practitioners are like mango flowers and fish eggs. A mango tree can give many flowers but only a few can ripen into fruits. The same is true for fish eggs. It takes hundreds or thousands of fish eggs for a few fish to make it. It is a truth, a pointer, reminding me that the life of practice is not an easy one. When our brothers and sisters traverse their obstacles and challenges, we should simply love them and never judge or criticize. Whether they are still in the monastci sangha or have already left, we must love them.

The life of practice is difficult. If we are still practicing, it means we are very fortunate, that we have merit. That merit is like something we had saved from years of working and thanks to it, even when we do not work we still have something to live on. This precious merit will sustain us on the long journey of a practice life. That is what is meant by “cultivating both merit and insight.”

During the early days of the European Institute of Applied Buddhism (EIAB), I applied an “Honor System” way of operating that is based on self-respect. It is what I had learned during my studies at the California Institute of Technology ( ). I understood that this training is based on the love and progress of each individual. We learn out of love and the need to understand, not out of any sense of pressure. That is why Caltech gave rise to many smart and gifted students. I try to build sangha by elevating the spirit of self-discipline. Self-discipline here does not mean being loose and unruly. It means self-discipline within the frames of rules and routines, in the spirit of the precepts and fine manners and following the sangha schedule. A growing tree needs space around it so it can absorb nutrients and air. Likewise, I give a lot of freedom to the brothers and sisters to fulfill their wishes.

Even though we have become a member of a community, we still have private aspects of our life and I respect that privacy. As for the communal aspects, we need to build them and contribute to them to create a common space for everyone to practice and live in. That common space is very important. Building sangha is to build a common space.

We should not have an idea of a perfect sangha. Sanghas since the Buddha’s time have had this or that issue and sanghas in times to come will also be like that. That is suchness, reality as it is. Looking into it, we see that things manifest when conditions are sufficient, and they hide when conditions are no longer sufficient. I also base my work of sangha-building on that principle. We do our utmost–what manifests will be the fruit of many generations of causes and conditions.

There were golden times when the sangha was strong and Thay went on many teaching tours. That may be the blooming of a lotus that has gathered together conditions of many lifetimes. After blooming, it returns to the mud. This has always been the case. Our sangha will also one day return to the mud. This is the truth of impermanence. It will be hidden in the mud, waiting for conditions to change amidst the miraculous course of life, waiting to form the next flower.

When we look at life this way, we open our hearts to accept it. Whatever we do, we do so with all our heart. Whatever the sangha can do, it does; be it joyful or not, be it successful or not. The important thing is that the Dharma continues to flow. The teachings and practices must flow continuously because that is what can change the sangha and change life. We ourselves have to be the living Dharma, we have to change. To practice is to face ourselves, to face our unwholesome habits in order to transform them. It is not about looking at the unwholesome habits of others. We see that when we can do this, then we can wish the same for others. As long as we cannot change ourselves, do not expect to change others. I believe that is the best way to build the sangha.

Serving and practicing are one

Dear brother, please share with us your insights on the relationship between practicing and serving.

To practice is to open our hearts to give rise to selflessness, loving kindness, and a deeper awareness of life. Those are the elements of spirituality for a practitioner. That is why it is very difficult to practice! So much more difficult than writing a doctoral thesis. To change a course of action, a habit, requires a great deal of determination. Changing ourselves is no easy feat.

Only when we serve in a way that nourishes love and opens the heart is it true serving. When we work, our habit energies manifest and we have a chance to practice with them. If we just sit in our study room–no one approaches us, no one makes us angry or sad–what is there for us to practice with? If no one suffers, how can love arise in our heart? When we join the schedule, practice Dharma sharing, listen to and be in touch with suffering, we can open our hearts to share with people around us. In those moments love manifests and grows in us and that is how we practice. In this way, serving is also practicing.

In my first year as Thay’s attendant, he never allowed me to stay back and attend to him during meals. He said, “Leave the food for me and go out to be with the lay friends. They really need our presence.” Sometimes I came out a bit late and only a few lay friends were left. But I still sat there to be present for them. Thay also encouraged me to join Dharma sharings. When we make sacrifices or dedicate ourselves to someone else’s welfare, we naturally come to understand and free ourselves more. It is not only by taking care of ourselves that we can realize freedom. When a candle is burning, its light touches everything in its vicinity. The hottest part is the candle wick and that heat returns to melt the wax, allowing the candle to continue to burn and shine. We are the same. When we serve others, when we bring all our energy to shine light in the darkness, that energy will come back and melt the “wax” in us. We become a free person thanks to serving. That is why to practice is not just to take care of ourselves, but also to serve. This is selflessness, this is humanity. We will find that then we are the one who receives the most.

If a candle is not lit, it is not truly a candle, but only a block of wax. A candle needs to be lit and in the action of burning, it becomes a real candle. A true practitioner is the same. We have our true nature, our purpose, and our action. We have already found our form in that of a practitioner. But if we cannot radiate the energy of peace and happiness to help others change their lives, then we only have the form, we are only the wax. We need to turn the wax into light. The path of service is what creates the elements of a practitioner. From wax we become light and are no longer just wax. That is why in Plum Village, we practice while we work. If we do not practice while working, we are not a true practitioner. To practice or not, it is up to us!