Working on “The Tet Times”

Brother Chân Pháp Hội

Brother Phap Hoi has been connected with the Plum Village newsletter for many years. This year’s newsletter editorial team had the chance to sit down with him to listen to him recount some memorable moments. The following is an excerpt from the interview.

Memorable moments

The Plum Village newsletter’s editorial team works to create a plate of spiritual food to offer to the world. Many people respect Thay, wish to learn Thay’s teachings, and at the same time are interested in knowing about the sangha’s activities during the past year. Thay always placed great importance on this spiritual food. In fact, Thay was the chief editor, and a very careful and serious one, of the annual newsletter for many years. Along the way, Thay has shown us many things about how to create this kind of spiritual food.

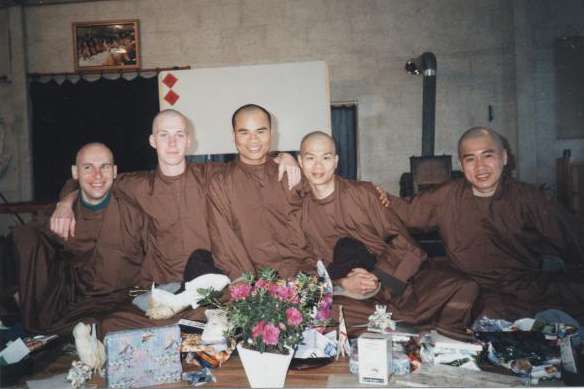

I was fortunate enough to be involved with the newsletter from early on. After ordaining in 1997, I followed in the footsteps of Brothers Phap An, Phap Kham, and other elder sisters and brothers in assisting Thay with the 1998 newsletter. I felt that Thay expended a great deal of energy and spirit on each article, editing word-by-word and phrase-by-phrase. This helped us to understand the newsletter’s essence and how to express the Plum Village style.

Thay was very happy that the newsletter only published positive, high quality news and was not interspersed with advertising. The content came not only from Thay but also from the insights of the practice of his monastic and lay disciples. Therefore, the newsletter expressed, from many different angles, insights on happiness in the practice, how the sangha was contributing to the world, and also contained archival material: accounts of Thay’s teaching tours, or the first steps on a new land to continue the spiritual ancestors there, or new ways of applying the practice… were all recorded. These later became key elements in documenting the formation, development and history of Plum Village.

The publication of the newsletter has become a tradition that many people look forward to and is lovingly called by its familiar name “The Tet Times.”Tet is the Vietnamese word for the Lunar New Year celebrated by many Asian and international communities around the world. Thay hoped for it to be a gift for the Lunar New Year, so we usually published it before Tet, in time to print and post to everyone. The editorial team therefore was also under some time pressure.

Thay was very active and open to new and more effective ways of working. Even though the newsletter is only published once a year, it is of very high quality. Its content carries the flavor of Zen as well as realistically describing the process and results of Plum Village’s socially engaged actions. Thay placed a great deal of energy into calling for support for charitable work. It also shows that practitioners are not only focused on our practice but also help and contribute to the world.

I had written a short article before I ordained about my happiness living in the sangha. The article was very naive, just listing my joys of being immersed in Plum Village life. I described how we practiced, what my room was like, how I lived, how happy I was with it, and an anecdote about a cat that could not bear the winter cold and sought warmth in my room every night. Br. Phap An also had the creative idea to publish a Shining Light letter, which had been given to me by the sangha, but with the name disguised. Back then, the vivid realities of sangha life were often reflected in the newsletter in that way.

Through the process of creating the newsletter, the editorial team had the chance to learn from Thay and to be with Thay. Thay was a very professional editor and an excellent one. There were times we were under pressure and our energy was no longer fresh. We did not recognize this, but Thay did. Even though it was close to the deadline, Thay still said, “Now, let’s take a break. Don’t do anymore. Let Thay fry rice for everyone.” Work was never as important as the practice of Thay’s disciples. Working with Thay was not just about learning editorial skills, it was also learning how to take care of ourselves and how to be happy while working. That was the important thing. We can also apply this spirit to working with Thay’s books. Those who had the opportunity to work with Thay on his books and the newsletter learned much about how to express our spiritual life through them.

When I came to Plum Village, I brought with me a new Vietnamese font software. The font was very beautiful and easier to use with computers. At that time in Plum Village we were using a very old Apple Macintosh. The Vietnamese font in it was usable but had many limitations. Thay was designing the Daily Chanting Book using the old font. The lay friend in charge of the computer suggested installing the new font. Sr. Thoai Nghiem volunteered to re-type all the sutras using the new font and she had to do so quickly, therefore even though there were still many errors, she had to overlook them in order for the text to be converted into the new style. Back then computers did not have font conversion systems like they do now and we still needed many humans to correct the grammar and spelling. I am from the North of Vietnam where the Vietnamese was very standardized, so I am quite comfortable with this kind of work, which Thay called “worm catching.”

Thay taught us what words to use so that the language was in keeping with Plum Village principles. Not every word could be used. Thay himself paid great attention to that. Even though Thay had a deep mastery of language, literature, and Vietnamese culture, he was always willing to accept and learn from his disciples new ways of using language. I saw that as a disciple, I benefited greatly from Thay and Thay was also always at the forefront of learning along with his disciples.

Thay was not afraid of using the dictionary. With words that carried different meanings, Thay went in search of their roots and their specific definitions to ensure that they were used correctly. At times, Thay was very insistent on using the meaning he wanted even though people could not understand it yet. For example the word awakening in Vietnamese is tỉnh thức. When Thay returned to Vietnam after many years he discovered that due to typing or copying errors, many people understood it as tính thức (consciousness) and interpreted it accordingly, leading to misunderstandings.

Sometimes I thought I understood what Thay’s intention was, but it turned out to be otherwise. One year, Tet was approaching and the sangha was joyfully making preparations. A small group and myself joined Thay to work on the newsletter. Thay edited the articles with all his heart whereas I, being young, wanting to play and waning in interest, worked quickly and half-heartedly. Normally Thay only signed “nh” on the draft manuscripts. That day after returning from an outing, I received a manuscript with his full signature, “Thich Nhat Hanh.” I was very surprised and scared because I understood then that Thay took even the drafts very seriously. I am the only person to have ever received Thay’s full signature on a draft manuscript. I tried to understand the meaning behind it–I was not working wholeheartedly and I was reminded of it. Thay could go over one article eight to ten times, refusing to ignore any errors if they were still there. At the time I was still busy with playing and did not work wholeheartedly. Later on, the incident became a memory between teacher and disciple. Perhaps this will go down in Plum Village history as a “one and only” occurrence.

I always collected the manuscripts with Thay’s signature and stored them in the Plum Village archive. Later on, I had to leave France for visa reasons and was away for twelve years. The sangha went through so many changes during that time, including to the storage areas, and I was not able to find the manuscripts again.

In the past I also collected the draft calligraphies of the parallel verses that Thay wrote (on oblong wooden plaques) for the meditation halls of each hamlet. Thay worked on the parallel verses wholeheartedly, carefully balancing the words and verses. They were outstanding and admired by everyone. In terms of form, Thay also had to practice to write beautifully. Thay would first try it out on a piece of paper to see if there was the right amount of space between the words and in the surrounding margins. Then Thay wrote each word on a piece of paper, positioned the paper on the wooden plaque, and took a photo of each word. I was able to collect these drafts. They were sometimes more valuable than the final versions because they were unique, whereas the final versions could be reprinted in their hundreds and thousands. I was very interested in the drafts because I could feel Thay’s heart, energy, and reverence in every detail. Although some words required more space than others, Thay could always balance them out wonderfully. Therefore, while working with Thay on books and the newsletter, I learned and grew a great deal. At the same time, I knew that I was not yet able to fulfill Thay’s wishes for me.

Later on I stopped working on books so that the opportunity could be given to others, and I worked in other areas of the sangha. Once a sister, after compiling one of Thay’s books, brought it to him to edit. Afterwards she asked Br. Phap Niem and me, why had she not received any praise from Thay this time? The two of us laughed and told her it was fine; it was a chance for Thay to train us to be happy while working with the books and to see it as a part of our practice. Thay often praised us when we first began our work. But afterwards we had to know how to work happily with whatever Thay had entrusted to us, and not to wait for praise before we could be happy. According to the practice transmitted to us by Thay, we must have happiness during our work and not wait until its completion. That is the essence of the practice; it is not merely about the work.