Taking Care of the Sangha

Brother Chân Pháp Khâm

Brother Phap Kham ordained as Thay’s disciple in 1987. Since 2005, he has been practicing, teaching, and taking care of the sangha as a senior Dharma teacher in Asia. Currently he resides in the Asian Institute of Applied Buddhism, Hong Kong.

In Old Path White Clouds, Thay taught that the harmony of views means to exchange and share understanding and knowledge with each other, and not to hide understanding only for oneself. In this way, everyone can learn and understand together. He encouraged the sangha to share our views with each other.

Listening to the sangha

Thay always listened to suggestions from the sangha. The sangha consulted with Thay, and he also consulted with the sangha when dealing with various matters. The Caretaking Council (CTC, ban chăm sóc in Vietnamese; also formerly known as ban điều hành - “Executive Council”) was born in this spirit. In April 1999, Thay asked the sangha for ideas on how to organize sangha life so that studying and practicing could bring more happiness. Some brothers and sisters gave suggestions to Thay. He then asked the sangha to review these suggestions. This article documents the birth of the Caretaking Council.

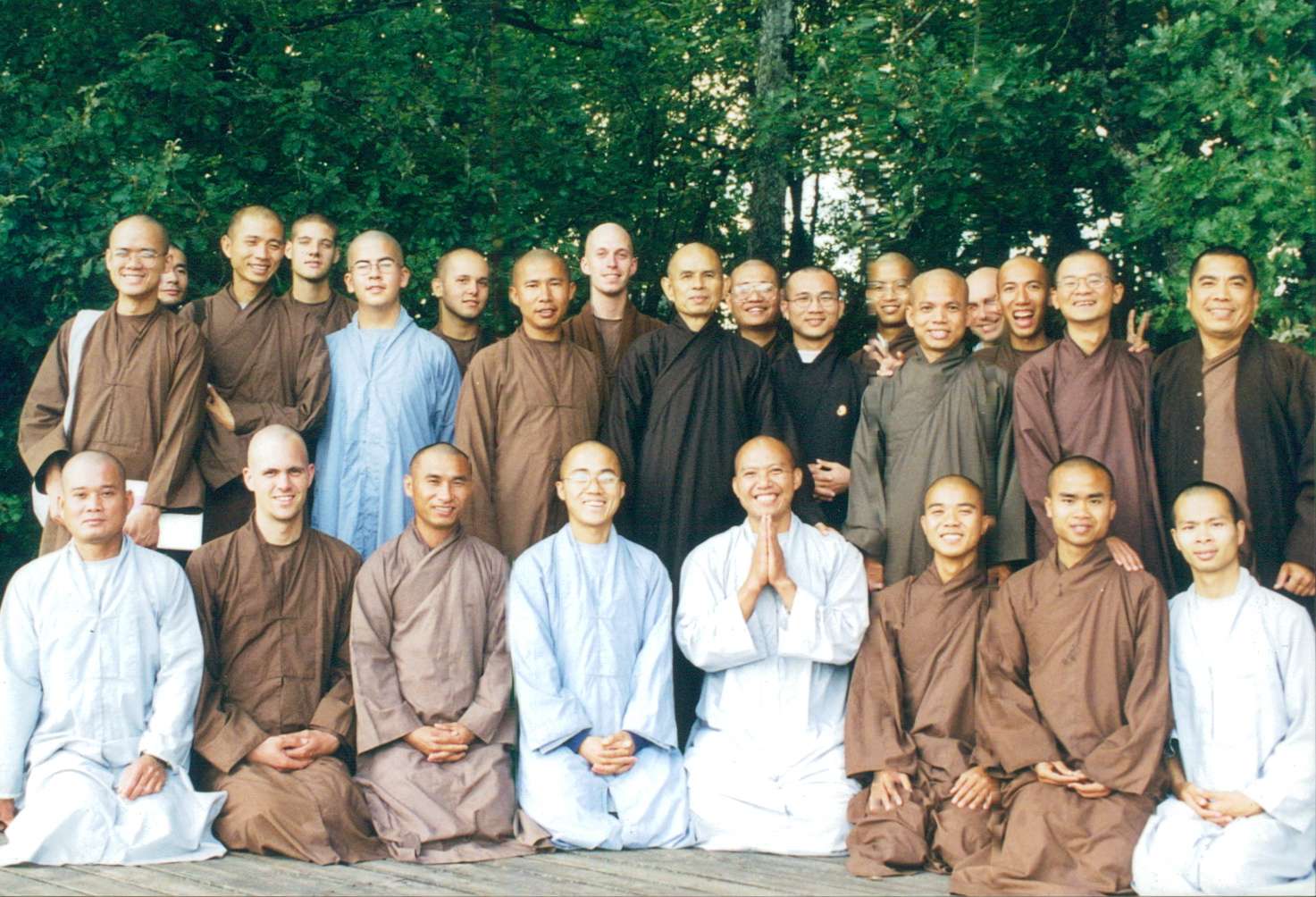

The Plum Village monastic sangha was established in November 1988 with the ordination of Sisters Chân Không, Chân Đức, and Chân Vị. In 1991 there were three monks and nine nuns, which grew to five monks and eleven nuns in 1992, and ten monks and thirteen nuns in 1993. The number of monastics increased slowly. By April 1999, a total of forty monks and forty-five nuns were ordained with Thay.

Brother Nguyen Hai was appointed abbot of Dharma Cloud Temple (Upper Hamlet) in 1996; Sr. Trung Chinh was appointed abbess of Loving Kindness Temple (New Hamlet) in 1996, and Sr. Dieu Nghiem the abbess of Dharma Nectar Temple (Lower Hamlet) in 1998. Around that time in Vermont, Plum Village established Maple Forest Monastery for monks with Br. Giac Thanh as the abbot, and the Green Mountain Dharma Center for nuns with Sr. Chan Duc as the abbess.

Back then, the abbots and abbesses coordinated various work in the sangha with the help of the work coordinators. The number of non-Vietnamese brothers and sisters had grown greatly and different understandings of monastic life and ways of living due to culture had emerged. The “Vietnamese” monastics back then were all overseas Vietnamese who had lived in the West, mostly from the US, Canada, France, Germany, the Netherlands, and the UK. They were more or less bridging two cultures. Right from the start, the Plum Village monastic sangha was not purely “Vietnamese” in terms of living style or ways of practice. Those with multicultural skills were more likely to adapt to the Plum Village environment.

The sangha as a miniature society

Difficulties prevalent in society are also there in the sangha. Monks and nuns are people who are committed to following a path of liberation. The difference is the environment of practice. That may be why we have more opportunities to identify our difficulties, and to sooner and more smoothly find ways of transformation than if we remained in a lay environment.

Around spring 1999, there were disagreements about how to live the monastic life amongst some brothers in the Upper Hamlet. I do not know if Thay was also concerned about anything on the sisters’ side. Thay convened a meeting in New Hamlet with all three hamlets. He listened to each brother and sister’s views about the ordination of Westerners, how the sangha handled the disrobing of some monastics, the relationship amongst elder brothers and/or elder sisters, and a few other things. Thay encouraged everyone to speak out about everything that was happening in the sangha for the community to look into together. During the meeting, Thay asked what percentage of harmony the brothers and sisters expected the sangha to have. Br. Nguyen Hai said about 80 percent. Thay smiled and said that was a little too high–about 60 percent harmony is good enough. That speaks to the fact that having different opinions is normal in life and in the sangha. It is important to accept differing opinions and come to the best possible solution together.

After that morning’s meeting, Thay asked for the opinion of the elder brothers and sisters on an organizational model that might be more appropriate for a growing multicultural monastic community. That night, I, then still a novice monk, went to Br. Phap An’s room for a chat. Since my ordination in February 1998, Br. Phap Hoi and I often came to Br. Phap An’s room to work on computer-related things. The three of us had helped set up the computer systems and internet network for Plum Village. We often worked together on Lazy Days or during our free time. Br. Phap An asked me if I had any ideas. Before becoming a monk, I had already come to Plum Village regularly, and had helped to organize Thay’s teaching tours in the Northeastern U.S.. I was also a community activist outside of my daily job, so was quite familiar with organizational models.

I said that it was possible to organize the monastic community according to the city management model, which includes a mayor and a city council with members representing different localities. In this model, the abbot is like the mayor while the Caretaking Council (CTC), containing representatives of the sangha from Dharma teachers to bhikshu/bhikshuni and novices, is equivalent to the city council. The abbot or abbess, which at that time was appointed by Thay, had a longer office-term. The sangha appointed the members of the CTC and they would have two-year terms or serve multiple terms, with representatives from the western monastics.

Br. Phap An presented the idea to Thay and Thay called together the Upper Hamlet Bhikshu Council to consider the proposal. After a few days of discussion, Thay and the sangha agreed with the idea. The first CTC was established. The members were Br. Phap Ung (Dharma teacher), Brothers Phap Hien, Phap Son, Phap Hoi, and novices Phap Minh and I. In that first council, half the members were of Vietnamese origin (Br. Phap Ung, Br. Phap Hoi and I) and half were of Western origin (Br. Phap Hien, Br. Phap Son and Br. Phap Minh).

Initially, the Vietnamese name for the council was Ban Điều Hành. But Br. Phap Hien said it did not translate very well into English–the Executive Council, so he proposed to change the name to Caretaking Council, which translated into Vietnamese as Ban Chăm Sóc. The two names were used interchangeably until 2003 when we officially settled on Caretaking Council.

Son Ha (Foot of the Mountain Temple) was established around that time and Thay asked two elder bhikshus, Br. Giac Vien and Br. Thong Tang, to lead the practice there with the support of Br. Ananda (from Laos) and myself. I felt the name Executive Council was not so appropriate because of the two senior teachers. We can “take care” of the two elders, but how can we “manage” them? Besides, no one can manage others, they can only take care of themselves; caring for the people and caring for the work. For example, the phrase “current members take care of new members” is much better than “current members manage new members.”

The CTC is based on the principle that members can contribute their talents and services to the sangha. The sangha is their playground. Apart from the practice, there are many people in the sangha with specialized skills in a variety of areas such as administration, information technology, cuisine, horticulture, journalism, etc.

Discovering talents

In the 2013 Annual Rains’ Retreat, Plum Village Thailand organized skills workshops for young monks and nuns who took care of the children, teenagers, and youth (Wake Up) programs. Sr. Toai Nghiem (mother of Br. Phap Lam, Phap Anh, and Sr. Loc Nghiem) asked whether there could be workshops for older monks and nuns. An essential skills training class was then opened for the brothers and sisters responsible for the meditation hall, cleaning, cooking, gardening, and recycling, etc., who often guided retreatants during service meditation. It is not only those in the children’s program, teens’ program, or giving Dharma talks who are “instructing.” Everyone has the skills and ability to contribute to the sangha. As the Vietnamese proverb goes–engaging people is like utilizing wood–the CTC needs to discover and allow those talents to manifest.

How the CTC runs and its relationship with the Dharma Teacher Council and the abbot or abbess is described in Thay’s book Joyfully Together. The CTC is like a country’s Council of Ministers, which includes the Prime Minister, Deputy Prime Minister, and other ministers. The work coordinator is like the Minister of Labor, ensuring that everyday tasks are delegated and that no one is “unemployed.” Ministries are like specialized departments, such as Finance, Guest Office, Foreign Affairs, Visas, etc., while the Dharma Teaching Council has the main role of guiding the study and practice. The abbot’s main role, or more broadly the Abbot’s Office because it includes the deputy abbot and assistants, is to take care of the spiritual life and internal affairs of the sangha. As Thay said, “The abbot is someone who can be approached by anyone.”

Thay often compared the role of the abbot to that of the Queen of England. The Queen does not run the country–that is the role of the Prime Minister–but she is loved and trusted by the people. Dharma teachers can join different departments or committees to help the sangha and have the opportunity to be close to and to train the younger monastics. When the three branches of the CTC, the Dharma Teacher Council, and the Abbot’s Office work with clear roles and responsibilities and mutually support each other in a spirit of harmony, the practices and activities in the sangha can flow very smoothly.

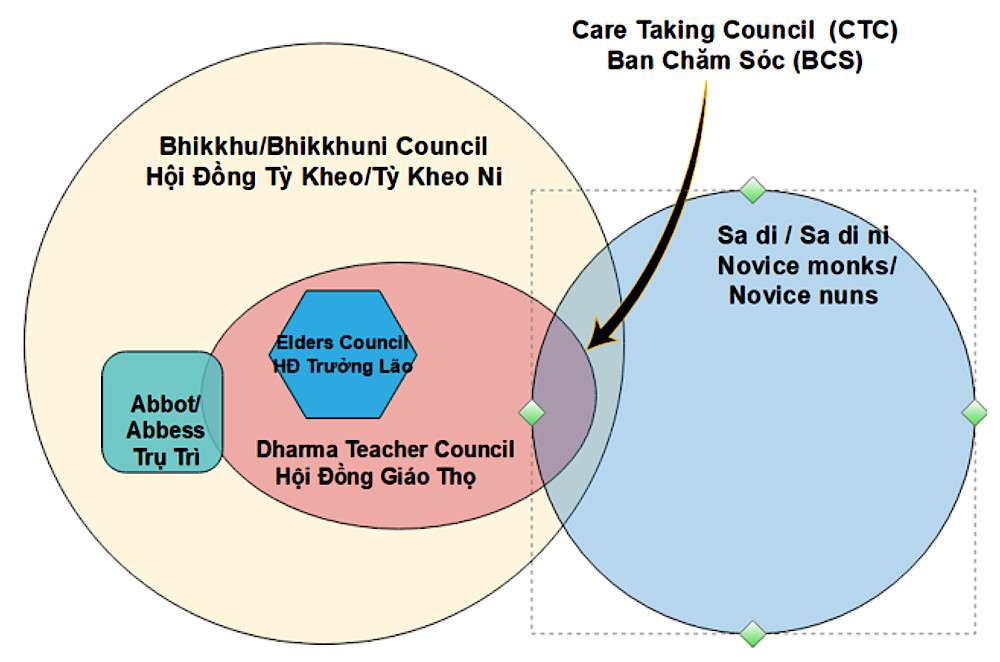

The basic model of the relationship between the CTC, the Dharma Teacher Council and the Abbot Office is shown below. The Bhikshu/Bhikshuni Council is like the parliament, making policies and bringing proposals for the whole sangha. It appointed the CTC and authorized CTC to carry out assigned tasks.

In those days, there was a tendency to think that the young monastics in the CTC were appointed for training purposes. This led to the requirement that CTC decisions had to be approved by the two other councils. It created more work and took away the CTC’s decision-making sovereignty. The three branches had already stated the issues that required joint decision and the CTC was authorized to carry out work that did not require further approval. The important thing was for the Bhikshu/Bhikshuni Council to appoint responsible and skilled people to positions in the CTC. In principle, the CTC should know clearly what its responsibilities are, and whom to consult when needed.

Thay mentioned the role of elder monks and nuns in the Council of Elders, which combines the traditions of seniority and democracy. Members of the Council of Elders were usually senior Dharma teachers. This Council’s role was to give advice on sangha affairs and help to resolve matters that need the virtue of the sangha, as the Buddha taught in the Seven Methods of Ending a Dispute and the Seven Methods of Non-Regression. If there were matters that needed immediate resolution and it was not possible to convene a Bhikshu/Bhikshuni meeting, representatives from the Council of Elders, the CTC and the abbot could consult with each other to make a decision.

On one occasion, the Upper Hamlet was hosting a Thursday Day of Mindfulness. The weather was beautiful, so the CTC proposed to have a picnic lunch. Thay did not know about that decision because no one had come to ask him for permission. Thay asked the sangha to eat in the meditation hall as usual. In this case, the CTC could have done better. The schedule of mindfulness days was decided and fixed by all three hamlets. To make changes, it was necessary to first consult with the Dharma teachers, the abbot, and the CTC. If there was an agreement, then the next step would have been to ask for permission from Thay and if Thay agreed, then it could be changed. The CTC was (and still is) authorized to organize the day of mindfulness, but not to change the schedule.

The spirit of “harmony of views” has inspired and given rise to rich and diverse programs of study and activities for the sangha. Programs such as the Happy Farm and the Wake-Up Movement also came about based on the ideas of sangha members. The establishment of the Caretaking Council is just one of those contributions. There remain many opportunities to creatively contribute to the sangha.