Dharmacharya Shantum Seth

Meeting Thay

When I first met Thay in 1987 he was sixty-one, a couple of years younger than I am now. Yet it seemed to me then and seems to me still, that he had already got to where he wanted to go, whether it was in his form of Engaged Buddhism or his personal awakening. I can imagine him smiling if he were to read this, and gently saying, “Shantum, the whole point of this practice is not to go anywhere, but to be in the here and now.”

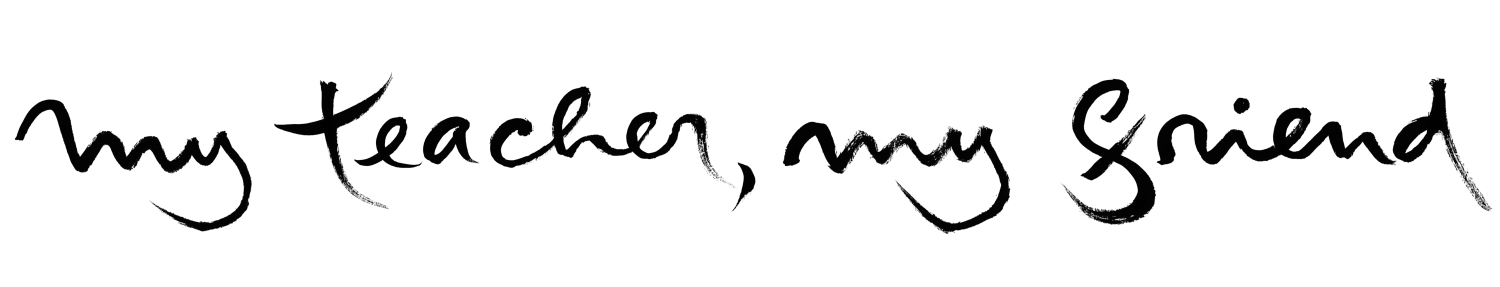

Our first meeting was at the Ojai Foundation in California. He was to lead a week-long retreat for artists there. More than a hundred of us were seated under a large oak. Few of us had even heard his name before and I remember everyone referring to him as ‘Kick the Can’ (because they did not know how to pronounce his name).

I was helping with recording the event, and as I was setting up the equipment. I looked up and saw a monk in simple brown robes gliding towards the tree, which everyone called the “Teaching Tree.” He walked with gentle deliberation. Involuntarily, we left whatever we were doing and rose from our seats and bowed to him. He had an extraordinary presence.

Everything he did and said was very simple. He sat still, we listened to a bell, he taught, and then he walked. For years I had been searching for some way to be peaceful, and now I could feel that sense of peace with each step and each breath that we took with him. I did not think he noticed me at all, but when we were seeing him off, he looked directly at me and said as his hands gestured a namaste, “Bring the Buddha Dharma back to India.”

The first pilgimage to India

This encounter stayed with me. When I returned to India a few months later, I found I really wanted to see him again. On impulse, I wrote to him. I offered to host him, should he ever want to visit India. But the letter lay on my desk for another three months before I found the confidence to post it. To my surprise and joy he responded. Could I organise a Buddhist pilgrimage for him and thirty of his students? I jumped at the chance to connect with him again. We started in Delhi, at our home at 8 Rajaji Marg. My family was all there, slightly sceptical but very curious. Thay sat with us in the garden by the lily pond, where he showed us how to walk with his kind of intense mindfulness. My parents and siblings silently followed in his footsteps. I think they could not help but feel his magnetism.

The Buddha as a human, not a god

It was wonderful to hear the stories and drama of the Buddha’s life through Thay’s eyes. The Buddha to him was not a God, but a real person, comfortable with people from all walks of life, able to connect with beggars and farmers, rich and poor, young and old, doctors, teachers, Dalits, Brahmins, kings, prostitutes, and even with animals, insects, trees, crops, and flowers. Thay was like a happy and curious child meeting his teacher everywhere–meditating in the same caves and rocks the Buddha may have sat on, crossing the same rivers, eating the same food and greeting the children, descended from the children the Buddha met. But his favourite place was Vulture Peak, the hilltop in Rajgir from where the Buddha loved to watch the sunset.

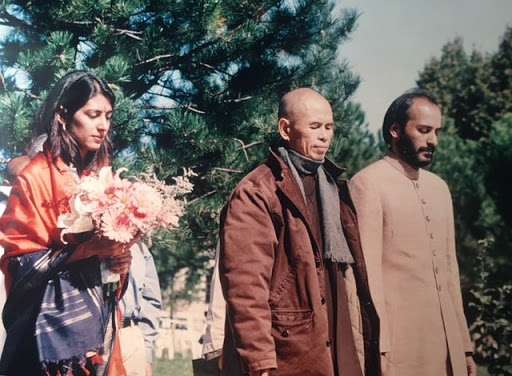

For the next thirty-five days I traveled with Thay through Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. I had been to some of these sites before, since I had been brought up in Patna, but visiting them again with Thay was altogether a different experience. He had just finished writing the biography of the Buddha, Old Path White Clouds, and at each of these sites, he brought the Buddha alive to us. It was at Vulture Peak, Thay said, that his own Buddha Eyes had opened some years before. It was also on Vulture Peak he ordained his first three monastic disciples. It was here too that he transmitted his lay teachings that had been extracted from the ancient Buddhist texts and condensed to what he called the Fourteen Mindfulness Trainings and the Five Precepts. These trainings are a clear set of guidelines on how to live a good life–good in a simple, happy and peaceful way–in these confusing times.

We sat under trees and listened to Thay talk about the Buddha’s teachings. Thay held my hand without saying a word. At that moment I felt I was looking with his eyes and that everything is interconnected. I had never thought of these matters, but at that moment I understood what he was saying, that nothing is born and nothing dies. He turned to look at me and pointing to the turban on my head, he said, “Shantum, the matter of life and death is as urgent as if your turban is on fire.”

Full moon in Kushinagar

On a full moon night in Kushinagar, where the Buddha had died, Thay and Sister Chan Khong, who was the first nun he had ordained, shaved my head. They were eager for me to be a monk, and I wanted it too, but I was not sure. A few days later in Lumbini, Thay presented me with a monastic robe. I did not wear it, but I kept it for a few years. I felt that I was not cut out to be a monk. I wanted to be in the thick of life, with all the mess of relationships and daily struggles and not sheltered in a monastery. When I said this to Thay, he warned me that it was far more difficult to practice outside than inside the monastery, but he did not discourage me to marry. I remember mentioning to him once that I often find it difficult to make choices in different situations, especially when the competing options are all good. His answer, both simple and profound, has remained a constant teaching for me: “It does not matter what you do, but how you do it.”

A Plum Village marriage

When I decided to get married, I introduced Gitu, my wife to be, to Thay. He said she reminded him of Yashodhara. Gitu responded, with a naughty smile, that she would rather be Sujata, who had offered the young Siddhartha kheer before his enlightenment rather than Yashodhara, his wife whom he had left to search for the path of awakening. Thay smiled. In fact, when I did marry, he conducted the commitment ceremony himself. We only went to him for a private blessing but he insisted he would perform the ceremony himself before the whole community in the meditation hall in Plum Village, France.

He asked us to repeat, every full moon night, the vows of love that he had just given us, and we have never missed doing that for a single full moon night in the last twenty-five years. It has been a regular reminder of our vows and deepened our trust and understanding of each other. It has also been a wonderful way of enjoying the moon together and being aware of its cycle.

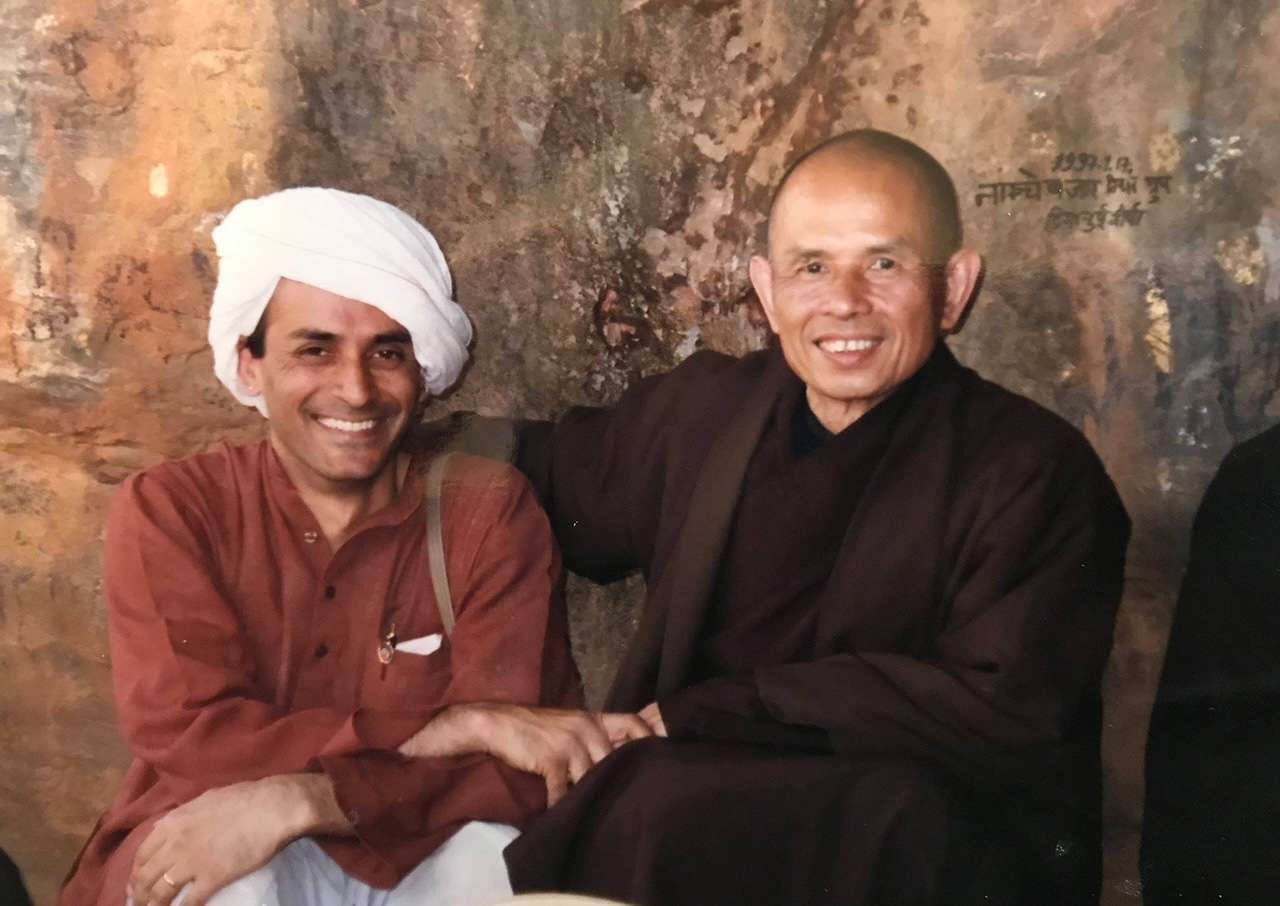

Thay returns to India

Gitu and I had been married nearly a year when Thay visited India again with a group of about twelve monastics. While we were in the village of Sujata, near Bodh Gaya, we visited a school where a large number of people from the village gathered. Thay was teaching on how to help people communicate. Gitu and I were sitting next to him and he turned to Gitu and asked, “What is it that irritates you or gets you angry about Shantum?” He asked her to act it out and speak openly in front of the village audience of more than a 100 people. Gitu felt too embarrassed to answer, but Thay encouraged her, saying that this would be a teaching to help in skilful communication. He suggested that Gitu use compassionate speech. So we did what we call “Dharma drama”! She said to me in a sweet way how it irritates her that I come late to meal times and allow the food to get cold. It was something many young women could relate to, she felt. Thay suggested to me that I do not react or say anything as an immediate response to what Gitu was sharing, and instead, to listen deeply; to know that it was important for Gitu to be able to share her irritation and for me to listen with my full attention, and to try and listen with a non-judgemental mind.

It was very touching. I am not sure what the others gleaned from this, but it taught me not only that I should not be late for meals and make people wait for me, but also to listen deeply and voice my appreciation for Gitu. It is not something that came easily to me being brought up in an Indian culture. Afterwards as I sat with Thay in his room sharing a cup of the oolong tea that he loved, I brought this up, hoping he may be able to cure me of the habit. I asked him rather naively “Thay, I am always late … what should I do?” His response was terse: “Leave early!”

Becoming a Dharma teacher

Gitu and I were with Thay in 1999 while he was on a tour in the United States. One day Thay came up to me and told me that my name had been recommended to be ordained as a Dharmacharya. This would mean that I would now be “transmitted the lamp” and be authorised to teach as a representative of Thay, who is the 42nd generation of the Chinese Zen Master Linji’s lineage.

I asked Thay who had recommended my name and he said “Thay.” I was pleased and surprised, but did not feel ready. When I told him my doubts, Thay said he had confidence in me. Gitu and I decided to go and live in Plum Village for a while so that I would feel more confident to take on my new role as a Dharma Teacher. Not that I could see Thay every day – he lived in a hermitage away from the monastery and visited twice a week to teach at one of the Plum Village hamlets, where hundreds of people would gather to hear him speak.

A Plum Village baby

He always treated Gitu and me with special fondness, often stopping to ask whenever he saw us how we were doing. When Gitu became pregnant, he would ask not only about Gitu, but also of the baby in her womb. He would ask me too if I was enjoying speaking with the baby in the womb. He also suggested reading the Lotus Sutra to the unborn baby. The Lotus Sutra is one of the most revered Buddhist texts that claims that anyone can awaken the Buddha in them. Once when we were sitting on the grass, he suggested that I speak to Gitu as if I was the baby in the womb. He explained that in his native Vietnamese, the womb is called the Palace of the Child, a refuge where the baby feels safe. I felt very embarrassed to do what he asked as there were many people sitting there with us. But there was no arguing with Thay so I bent down and addressed Gitu as the baby in her womb.

It was a most intimate conversation that developed. Thank you, I said, for carrying me in your womb and taking care of me. Thank you for nourishing me, for feeding me, for breathing for me. Thank you for taking me for a walk to watch the sunset each evening and describing the beauty to me. Thank you for speaking with me and loving me. Thank you for taking care of what you eat and drink and consume. I smile when you smile. I can feel your change of emotions and know when you are happy or disturbed. And how are you doing? Are you enjoying it? Is it difficult? How do you feel when I kick you? I asked as if I was the baby in Gitu’s womb. All at once, I could see that Thay and even the Buddha had once been babies in the womb, like me.

It was also to Thay that I owe the way I earn my livelihood. I was then working at the United Nations and decided to take only one dollar a year for my work and needed to find another way of making a livelihood. After my first pilgrimage with Thay, he had suggested that I organise pilgrimages in the Buddha’s footsteps every year. I joyfully accepted the challenge and at first was doing it once a year, but eventually this turned into my livelihood, and I have been leading this pilgrimage for more than thirty years now.

Since my first pilgrimage with Thay, I made it a point to go and stay with Thay for about a month each year, wherever he was; whether in Plum Village or in some other country where he went to teach. There have been many wonderful interactions with Thay the years thereafter, especially during his historic trip to India in 2008, but that is another story.

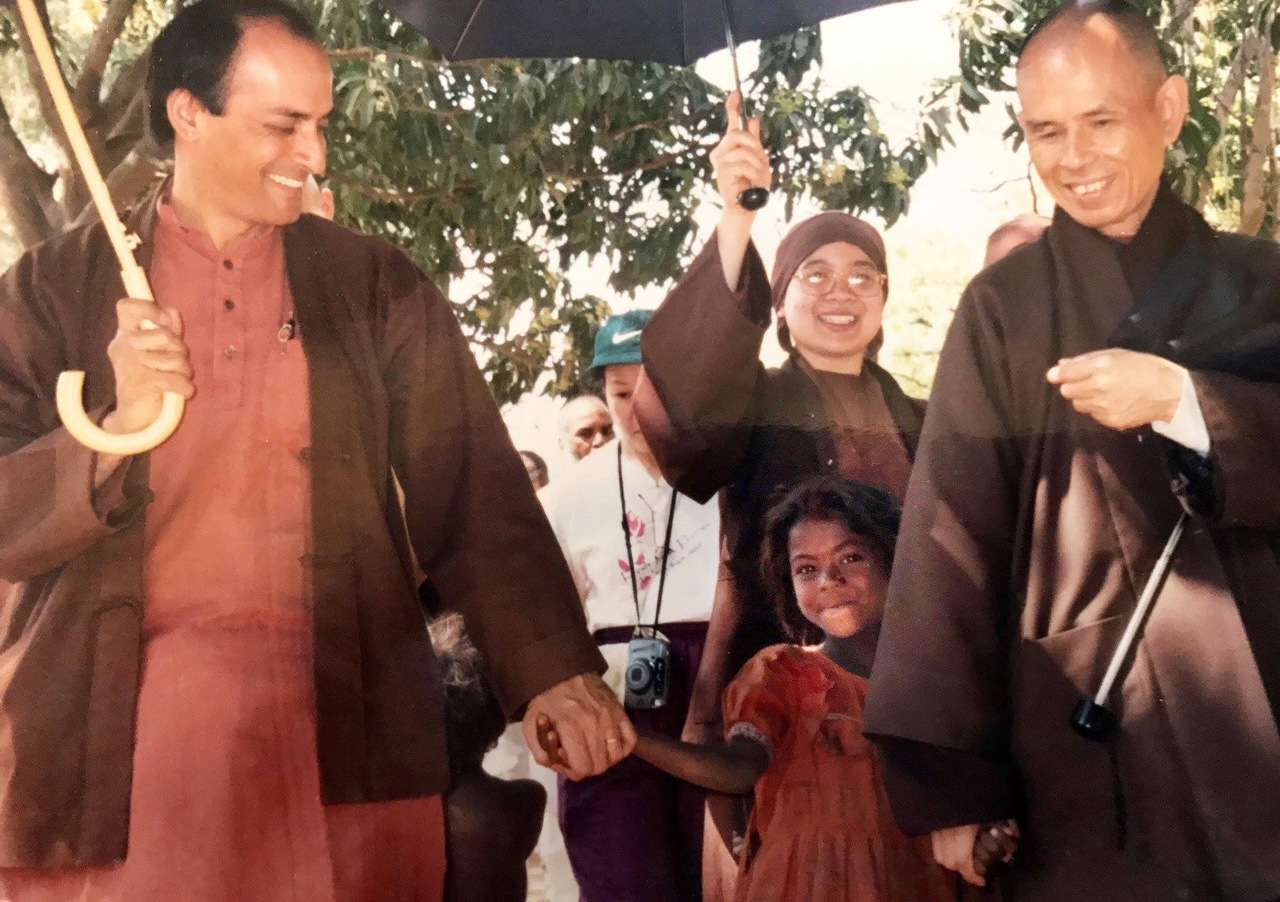

He has been my guide, teacher, and wise friend.