Returning to Lower Hamlet

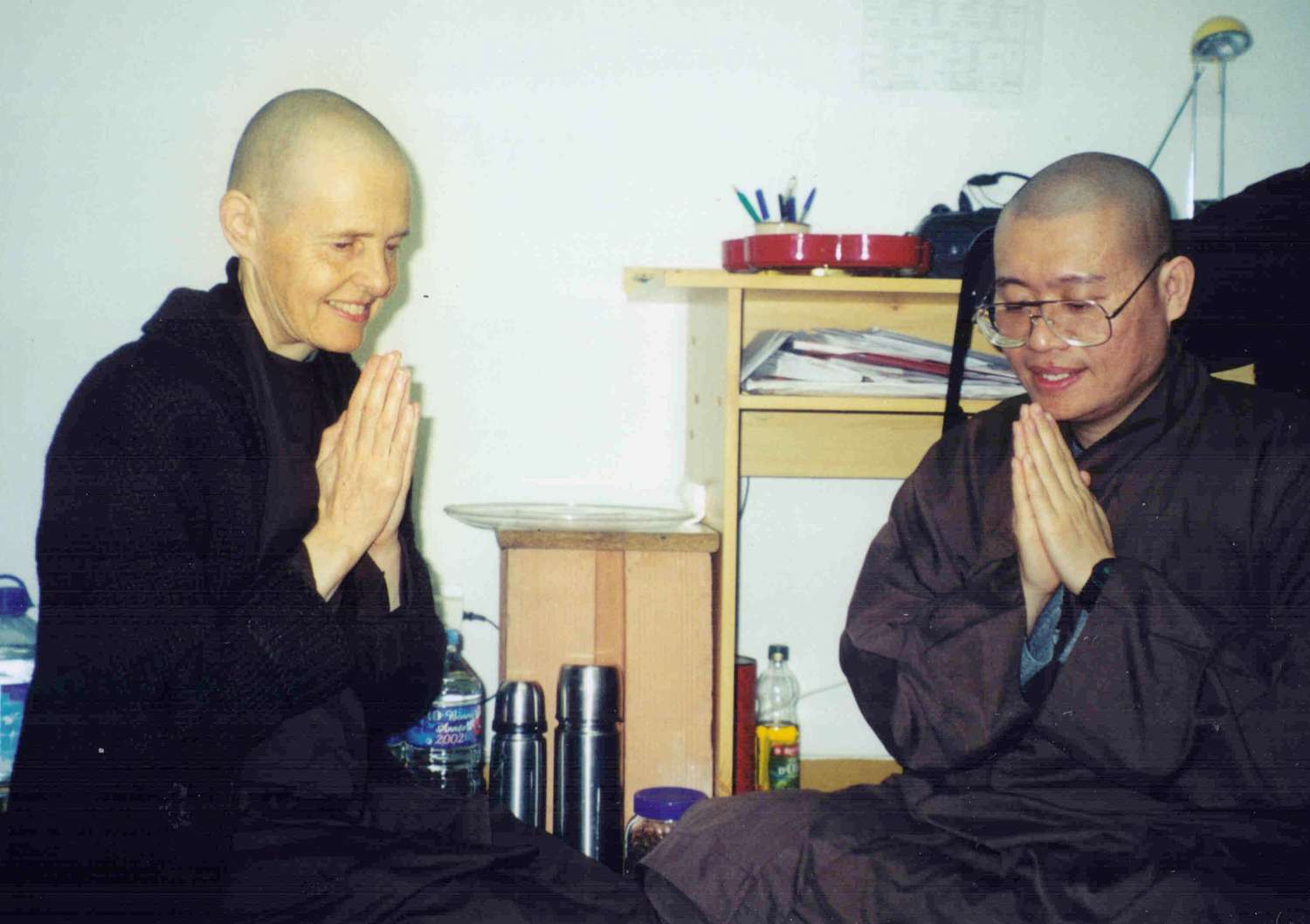

Sister Chân Đức

Here is India, India is here

I arrived in Plum Village on the first of July, 1986. A lay friend driving an old yellow Quatrelle picked me up at Sainte-Foy-La-Grande station. Three months earlier when Thay was in England at the invitation of myself and some friends at the Buddhist Peace Fellowship, he had suggested I come to Plum Village for a month. When I arrived in Upper Hamlet, Thay was sitting in a hammock, which was always slung between two trees opposite the Stone Building. He was wearing a grey ao vat hoTraditional Vietnamese short robes worn by monastic practitioners because it was a very hot day.

When I joined my palms to greet Thay, he said, “Here is India. India is Here.” I did not understand and I thought Thay meant, “The weather is very hot here, like in India.” Later, on reflection, I realised Thay meant something like, “My child, this is your spiritual home. You do not need to go to India to find your home.” Thay told me later that this was a quotation from a poem by the Vietnamese meditation master Vô Ngôn Thông of the ninth century.Tây Thiên thử độ, thử độ Tây Thiên (西天此度,此度西天 - 無言通禪師)

First impressions of Upper Hamlet

My first impression was how relaxed Upper Hamlet was. It was two weeks before the annual Summer Opening and preparations were being made in such a joyful and leisurely way. A bed had been prepared for me in a room whose name over the lintel was “Young Moon.” The bed consisted of four bricks, which supported at each corner a plank of plywood, covered by a thin piece of foam. In the following days I helped prepare beds like that for the guests who were to come.

Another impression was: This is a five-star hotel, because in the monastery where I had practised in India, we had been so poor. We had no running water, no electricity, and no beds. Here I had the basic amenities as well as a spiritual family to practise with, and a teacher who spoke English and French and could guide me in the practice.

Life in Lower Hamlet

After a month, I was allowed to go to Lower Hamlet for the last two weeks of the Summer Opening. I stayed in the Plum Hill Building, which had eight beds like the ones in the Upper Hamlet. I had a strange feeling of being at home when sitting under the centenarian oak trees and looking out to the north. The view was more expansive then because there was not yet the poplar tree grove. I experienced the same feeling when practising circumambulation in the Red Candle Hall and seeing the stones that made the walls. At that time, there was no plaster between the stones.

Around Lower Hamlet there was much more forest than there is now, and the 21 hectares that belonged to the hamlet had vineyards and many fruit trees. It was indeed a secret garden to explore. One day in the autumn in August, Thay picked blackberries and gave them to me, asking me to make jam. He must have known that my mother made bramble jelly every year so it was easy for me to continue her.

During the Summer Opening, by the side of the oak trees was the “Oak Tree Kiosk” selling all kinds of sweetmeats in the afternoon. The proceeds went to the poorest children in Vietnam. With this money, Sr. Chan Khong would buy medicine. We would put the medicine in boxes and send them to social workers in Vietnam. They would sell the medicine and give the money to those who needed it. We did not just send material things; every parcel also contained some exhortation to practise mindfulness.

After the Summer Opening, the guests went home and I moved into the Cypress Building. This building is now the kitchen, store, and dining room of the Lower Hamlet. At that time, the Purple Cloud Building was full of straw and dung left by the cattle that had inhabited it. The room I was given was quite large. It had a floor of baked tiles, a green porcelain wood stove, a chair, and a desk. I stayed there alone until Sr. Chan Vi arrived in May 1987.

Cypress Building had an attic. There were many buckets and basins up there to catch the rain. When it rained hard, there were never enough buckets in the right place and the rain would come through the ceiling and sometimes on to my bed. Plum Village did not have the money to repair the roof at that time.

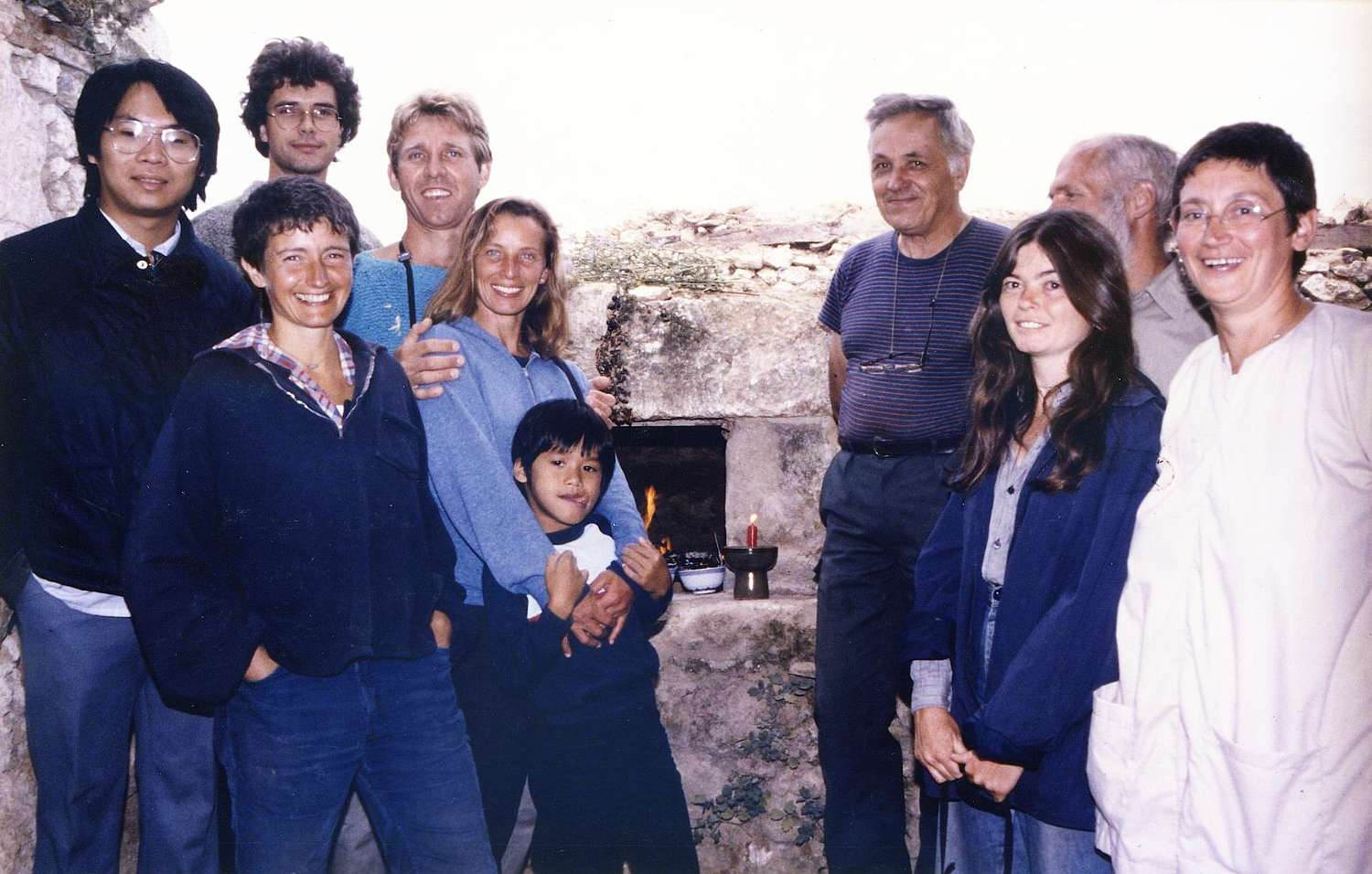

and Robert Naeff (third from right)

When I first came to the Lower Hamlet, there was a traditional brick bread oven. It was in a little stone building behind the Purple Cloud. It had been repaired by a Dutch Order of Interbeing member, Robert Naeff, who had knowledge of building this kind of bread oven, so we could actually make bread. You made a wood fire in the oven and when the wood began to turn into embers, you took them out and put them in a bucket. You had to be very careful doing this because if they fell onto the surrounding dry grass, it could cause a fire. Then you placed the uncooked bread in the heated oven. We had to try a few times in order not to burn the bread, but eventually we succeeded in making something edible.

We had a wonderful neighbour who lived in what is now the Cherry House. Monsieur Mounet made apple tarts and took them to the markets to sell. He had constructed his own gas-fired oven and he said after he had finished baking the tarts, the oven was still hot enough to bake bread, so I would bring my bread and bake it in his oven, which was much simpler.

Dharma music

For Thay, music and poetry were an important part of the practice. We did not have any English practice songs when I first came to Plum Village. Thay encouraged all his students to write Dharma songs. At first we thought we could never write a song but somehow Thay managed to water that seed in us. The first song I wrote was before I ordained as a nun. It came to me as I was washing dishes in the small, low sink that we had in the kitchen of. It was “Breathe and you know that you are alive.” Thay had been teaching the Anapanasatti Sutta. When I look at this song, I see that Thay must have taught this sutta in a very colourful and poetic way and I had already heard about Great Master Bamboo Forest (Truc Lam Dai Si) of the thirteenth century who told his disciples, “Whenever I pick something up, it is always new,” and that’s what gave rise to the last line of the song.

Taking care of the brothers

In 1990 after the ordination of Brothers Nguyen Hai, Phap Dang, and Vo Ngai, Thay told me to go and live in Upper Hamlet to keep an eye on the practice up there as there were no other elder monks yet. Although I had two younger blood brothers, I was a real novice in taking care of young monks. I considered my task was to make sure they came to the sitting meditation. There were also a couple of novice monks from a temple in the United States. I think there were five novices in all. Two of them were compliant to my wishes, but the other three thought it very strange to have a nun telling them what to do. One said it was like being in the army with me as the colonel! One day in frustration at the novices’ absence in the morning sitting, I entered the room of one of them and pulled back the sleeping bag from the sleeping monk. This is probably where my reputation for being an army colonel came from. Thay had recently introduced the practice of Beginning Anew, so we had to do it. One young brother told me that I needed to understand that he had stomach problems and that is why he did not come to meditation.

When I came to Upper Hamlet, I was inexperienced in building sangha as a family. Maybe because of my training as a schoolteacher, I was only aware of myself in relationship to the brothers as the one who had to remind them to practise. I was translating the History of Vietnamese Buddhism at the time. Any free time I had, I spent upstairs in the Stone Building doing this, rather than devoting myself to making a family atmosphere. I still had much to learn about how to be a good elder sister. This has been a learning process throughout my monastic life.

In 1991, fortunately Br. Giac Thanh arrived and I could be relieved of my Upper Hamlet duties.

Trusting the Dharma and the sangha

In my thirty-three years as a nun, I have certainly had challenges to face. What helps me most is my deep trust in the Dharma as the teachings of truth, and in Thay as the one who can transmit them to me. As the years have passed, my trust in the compassion and wisdom of the sangha has grown and this place of refuge always helped in difficult moments.

Sr. Chan Khong, my elder Dharma sister, has been a stable and compassionate guide for me. When I first lived in Plum Village, my practice was to nourish the seeds of happiness. Sr. Chan Khong was a very good example of someone who had been through so much and who could find so much happiness in little things in the present moment. I learnt more from her examples than from her advice. One thing that was very helpful for me was reminding me to smile every half hour. I had to keep an eye on the clock, but I really wanted to be able to do that. Sr. Chan Khong has taught me in difficult moments to be aware of all the things I have to be grateful for, right here and right now, and how to practise mere recognition in order to take care of unwholesome mental formations.

Now when Thay is no longer physically there in Plum Village, my trust in the sangha has deepened. Over the years I have seen how compassionate the sangha is. When dealing with a sister who has difficulties, rather than punishing and blaming, the sangha tries to embrace that sister. The sangha’s growth in compassion is thanks to the advice and guidance of Thay. Of course there are times when the sangha has to lay down firm guidelines, but that is done out of love. I also see how the sangha has the capacity to listen deeply to each other in a way that thirty years ago would not have been possible.

We certainly have our ups and downs but we can sit together, begin anew, and go ahead while understanding each other more deeply. Very often it has been the difficulties that have emptied me of pride and self-confidence, and filled me with non-self confidence. This is how I understand “the kleśa are the bodhi, the afflictions are the awakening.”

Some of the important moments of revelation seem to occur when I am sitting in a circle with other practitioners. I suddenly realize that I do not have a separate self and I can only be in relationship to others. When I first come into a circle, I usually arrive early and watch sisters coming in. As we become settled, I like to look around and feel my affection for each sister who is sitting there. I follow my breathing as I am doing this. I know that we all come from very different backgrounds and on the surface we all look and behave very differently. Nevertheless there is something very deep that connects us. It is rather like the trees in the forest where the roots of one are always connected to the roots of others. The simple fact that we live together twenty-four hours a day, and we have all made the same commitment to the monastic life seems to bond us in a special way.

Since I came to Plum Village, I have transformed, but I recognize I still have so many shortcomings. No one wants to do harm. But I can still unwittingly say something that causes trouble. I have to forgive myself because I did not know what I was doing. However, at the same time, I have to make a strong resolve to do better. When I first came to Plum Village I found it difficult to listen to someone pointing out my faults. I think I am better at doing this now. In the beginning I had trusted Thay more than the sangha. I have much more trust in the sangha now and I am able to see that Thay is in fact the sangha because the sangha is Thay’s masterpiece.

Gathering the fruits of practice

My fear of death has lessened and the teachings on the cloud have helped me. I remember when I was living in the Green Mountain Dharma Center; we had so much snow in the winter. One of the things we liked to do was to lie on the snow, stretch out our arms, and then move them back and forth. Then we would stand up and look at the image impressed on the snow – it was exactly like an angel. As I lay in the snow, I would see how the water in my own body and the water outside in the form of snow were not two separate things. This meditation on the six elements inside my body and outside my body helps me to see that I am not able to die in the sense of becoming non-existent. In fact there is no “I” anyway to die. In France where we do not often have snow, I see myself in the cloud and the cloud in me.

I have been in Lower Hamlet for about twelve months now. I left Lower Hamlet in 1996 to go to New Hamlet and then to Maple Forest Monastery in the U.S., so I was absent from Lower Hamlet for twenty-four years. There are places that have not changed very much, like the little path that leads down to what was my hut, the path behind the Dharma Nectar Hall, the Red Candle Hall, and the grand oak trees. Thay’s room in the Lower Hamlet where Thay would lie in the hammock after the Dharma talk and invite us to drink tea with him is one place where we can feel Thay’s presence very clearly. As soon as I practise mindful walking in the Lower Hamlet, the flavour of Plum Village thirty or more years ago is very apparent.

I remember one time in the Lower Hamlet when I was a layperson and we were preparing to get in the car to go to visit Fleurs de Cactus in Paris. I had a deep aspiration to walk just like Thay walked, so I tried it out for myself while waiting for others to arrive. Maybe at the time it was more outer form than content, but over the years, the peace and joy that come from walking like this are authentic. Thay’s steps in Plum Village are what have made the atmosphere of Plum Village sacred, and of course we all want to keep this sacred atmosphere alive by continuing to walk mindfully.

Letter to Thay, October 2021

Beloved and respected Thay,

Last night at about 4:00 a.m. I had a dream. Our international monastic sangha had gathered at a train station. Hundreds of us were all there together. Sr. Tu Nghiem (Sr. Eleni) and I for some reason did not have a ticket. I felt it was urgent that we buy a ticket without delay. We went to the ticket office but it was closed. Then the man who sold tickets appeared. He was very kind and agreed to sell us tickets immediately. I worried that I did not have any money but the man said he wanted to give us two tickets for the price of one. I had exactly the right amount of money. With our tickets we went outside to join the sangha which was going up the steps to the train together. On seeing the sangha I could not believe how beautiful it was: even more beautiful than the wild-goose sangha that migrates over France in the autumn and spring in a stunning “V” formation.

When I woke up, I thought, I have seen Thay. The sangha is Thay; Thay’s lifetime creation.

I remembered the times I accompanied Thay on tours to China or Korea. We visited ancient monasteries with old attic libraries full of wood blocks from which the sutras were printed. On two separate occasions Thay had pointed out to me the gatha from the Vajracchedika Sutra:

Someone who looks for me in form

Or seeks me in sound

Is caught in an abstraction

And will not find me

For many years I have been caught in that abstraction, that misapprehension. This morning I have seen a much greater Thay.

Sometimes as an elder sister I need to be a teacher for my younger siblings. I need to practise signlessness in looking at them too and realise that Thay is in each of them.

Touching the earth in boundless gratitude,

your child,

Chan Duc