Meeting my Teacher

Dr. Hà Vĩnh Thọ

Dr. Ha Vinh Tho (Chan Dai Tue) is a lay Dharma teacher in the Plum Village tradition. He was the program director of the Gross National Happiness Center (GNH) of the country of Bhutan from 2012 to 2018. He holds a PhD in psychology and education from Geneva University, Switzerland.

I was born from a Vietnamese father and a French mother. I grew up in many countries, but mostly in Europe and I first visited Vietnam with my father in 1982. I was 31 years old.

Although I grew up abroad, I felt a connection to the country of my paternal ancestors, but it was limited because I had not learned Vietnamese as a child. My uncle Mr. Ha Van Lau was the ambassador of the Socialist Republic of Vietnam to France and lived in Paris, and when he came for working sessions to the United Nations in Geneva, he often visited us, as we lived nearby.

At that time, we lived in a community that took care of children with intellectual disabilities, and my uncle often told us we should create something similar, to support the disabled children in Vietnam. During this first visit to Vietnam, I met several members of my family, including one uncle who was a well-known Buddhist sculptor, and his son who was a painter. Both father and son had been students of Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh in the sixties and they asked me if I had had the chance to meet with Thay who now lived in France. I was embarrassed to admit that I had never heard of him – in those days Thay was not so well known in Europe yet.

When I returned to Europe, I wrote a letter to Thay asking if we could come and visit. His close disciple Sister Chan Khong wrote back a very friendly letter inviting us to come and visit the newly opened Plum Village center in south-west France. She also sent an English edition of The Miracle of Mindfulness that was published in Vietnam. I read the book with great interest, but for some reason it took us several years before my wife Lisi and I visited Plum Village for the first time in the late eighties.

When we arrived, we were right away invited to have tea with Thay and Sister Chan Khong, and we thought at the time that it was usual for newcomers to be invited to Thay’s hermitage. In fact, Thay knew many of my relatives because my family was also from Hue, his hometown. One of my uncles and his son had been close students of his, and had illustrated some of his books. Furthermore, Lisi also has a Swiss cousin that Thay had met in the sixties in the U.S., because he belonged to the first batch of Westerners who ordained as Zen monks in the San Francisco Zen Temple founded by Suzuki Roshi in California. So, arriving in Plum Village for the first time almost felt like coming to a family reunion.

The first time I heard Thay give a Dharma Talk, I was deeply moved, in fact more than once, I found myself crying while listening to the teachings. Not because I was sad, but because it touched my heart so deeply. I knew that until then, my understanding of compassion had been quite shallow, too theoretical, but when I was in the presence of Thay, I had a direct experience of lived compassion united with a wisdom so vast that he could express it in very simple words without losing its depth.

I knew I had met my teacher.

From then on, we went regularly for retreats to Plum Village, along with our children, and we had the chance to develop a very deep connection with Thay. For me it was also a wonderful opportunity to reconnect with my Vietnamese roots.

Thay was able to share with the world the best of traditional Vietnamese culture and through him, many Vietnamese felt proud of their origins and could share it with their children. They were reminded of their ancestral roots even while living abroad. His foreign students developed a profound admiration for the beauty and depth of Vietnamese culture and spirituality.

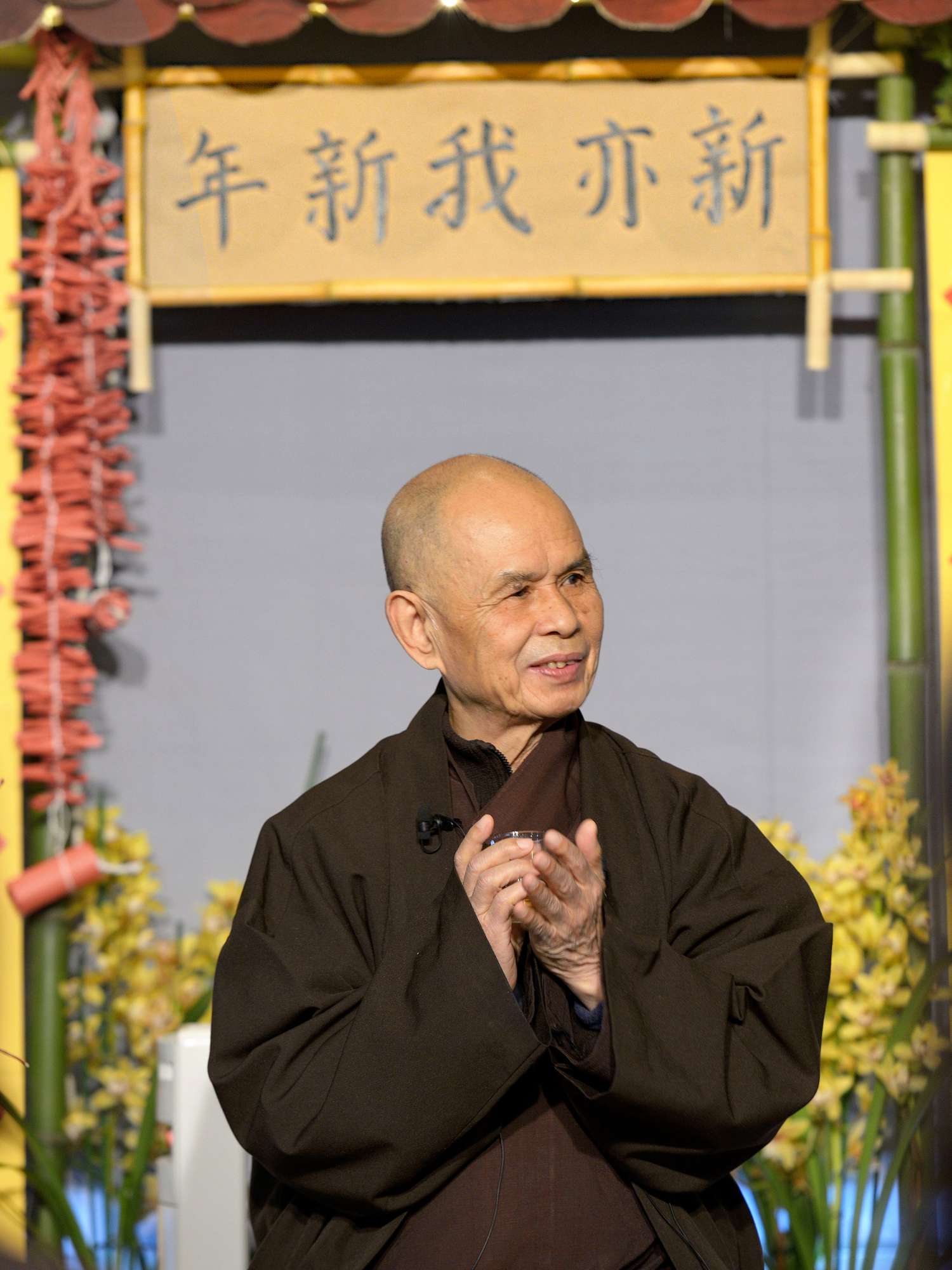

Photo by Jamie Hadnagy

As a child, we had an ancestor altar in my home, but it did not mean much to me. After visiting Plum Village and listening to Thay teaching on the importance of both biological and spiritual lineages; ancestor worship became very meaningful. To this day I have an ancestor altar in my home, and each morning I offer incense, fresh fruits and tea.

We were some of Thay’s first students to have a chance to go back to Vietnam at a time when few foreigners were visiting. Thay was happy to receive news and pictures from his homeland and especially from his hometown Hue, his root temple Tu Hieu and his many disciples and friends. When we came back to Europe, we gave Thay a book with many pictures we had taken for him from the places he knew.

In his Dharma talks Thay would often quote traditional Vietnamese folk tales, the Kim Van Kieu, figures from Vietnamese history such as King Tran Thai Tong who became a Buddhist monk, and great Vietnamese teachers such as Buddhist Master Khuong Tang Hoi. Therefore, alongside learning about the Buddha Dharma, his students also learned a great deal about Vietnamese culture and history.

Thay strongly encouraged us to develop educational projects in Vietnam, first for the children with disabilities and then also more widely. This is how my wife and I, with the help of some educator friends, created Eurasia Foundation. The two people who supported us from the beginning were Ambassador Ha Van Lau and Thay.

Looking back at the many years we had the chance to be in Thay’s presence and to receive his teachings, I am filled with a deep sense of gratitude; he never asked anything from us, never expected anything, left us completely free, but he was always there for us. He himself was a living embodiment of his teachings, I had the chance to meet him quite often on different occasions but he was always the same, when meeting with famous or important individuals or with a simple common person. He especially liked having children around him and when he practiced walking meditation, he often held the hands of the children. He offered everyone the same compassionate and full attention.

I was also impressed with how he was an amazing “Ambassador” for Vietnam. To many people around the world, he was a true representative of Vietnamese culture. When I moved to Bhutan at the Gross National Happiness Center, I wanted to invite Thay to visit the country. I discussed this project with the Prime Minister of Bhutan, Jigmi Y Thinley. The Prime Minister was very supportive of it and wanted it to be a State Visit. I also had a chance to offer a copy of the book The Art of Power signed by Thay to His Majesty the Fifth King, and he told me that he had read Thay’s book Old Path White Clouds: Walking in the Footsteps of the Buddha several times. The King even knew some parts of the book by heart and he held Thay in great esteem.

Unfortunately, the visit of Thay to Bhutan never happened. First we had to postpone it because of the national elections, and then when it would have been possible from the Bhutanese side, Thay’s health did not allow for it anymore. Nonetheless, Thay’s teachings and practices have had a major influence on the way we conduct the Gross National Happiness (GNH) programs, and mindfulness is a core part of all our programs. Therefore, in a way, although Thay did not come to Bhutan in his physical body, his Dharma body has been there and is still there, because much of the way we impart GNH is deeply connected with his teachings.

I would like to share two personal anecdotes to show how Thay was teaching us besides the Dharma talks and the formal meditation sessions.

Once, in Switzerland, I was walking with Thay. I had just come back from Vietnam and I was sharing about my visit to Tu Hieu monastery. He had not been back to Vietnam yet, and I was sure he would be happy to hear about his root temple, and so he was; but I guess I got a bit too carried away, and I was not really mindful of where I was, there and then. So, at one point, Thay stopped, made me stand still, smiled and pointing at the earth under our feet, said, “Tu Hieu is right here, right now,” and then we continued our walk.

Another time, I was having dinner with Thay and Sister Chan Khong, and I was sharing about the educational projects we were implementing in Vietnam. I was very enthusiastic and probably not very mindful of what I was eating. Again, Thay smiled, made a small gesture with his hand to stop me and asked, “Are you eating projects or are you eating rice?” I felt a bit embarrassed, but I was also grateful to be reminded of truly living in the present moment.

A true Zen Master, he was always attentive to help us live the mindfulness practice in every moment of our life, but he did so very gently and with humor and compassion.

When I heard of the passing of Thay, to be frank, I did not feel sad. I felt a deep sense of gratitude and love. I am aware what a blessing it is to meet such a great master in my lifetime. I do not feel that Thay is gone. He lives on in his teachings, in his many disciples; he has had a tremendous impact on this planet, he has brought so much wisdom, compassion, and a sense of ethical values to so many people all over the world. His spirit is more present than ever, and the people of Vietnam can be proud to have produced such a prominent son who has contributed to radiating the spirit of Vietnam in the ten directions.

offering Thay’s books to the Bhutanese royal family in 2012