Don’t Cover Your Monastic Life with Bells and Incense

Brother Chân Pháp Hải

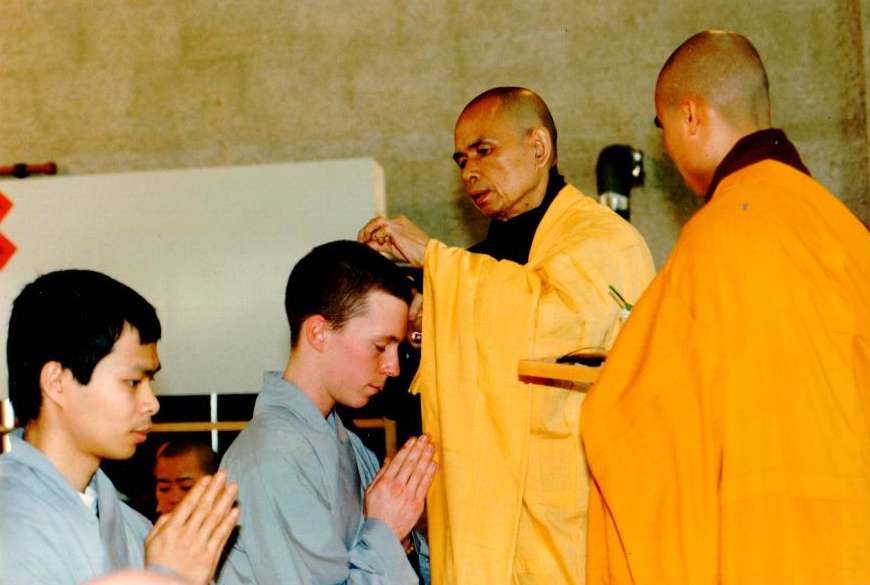

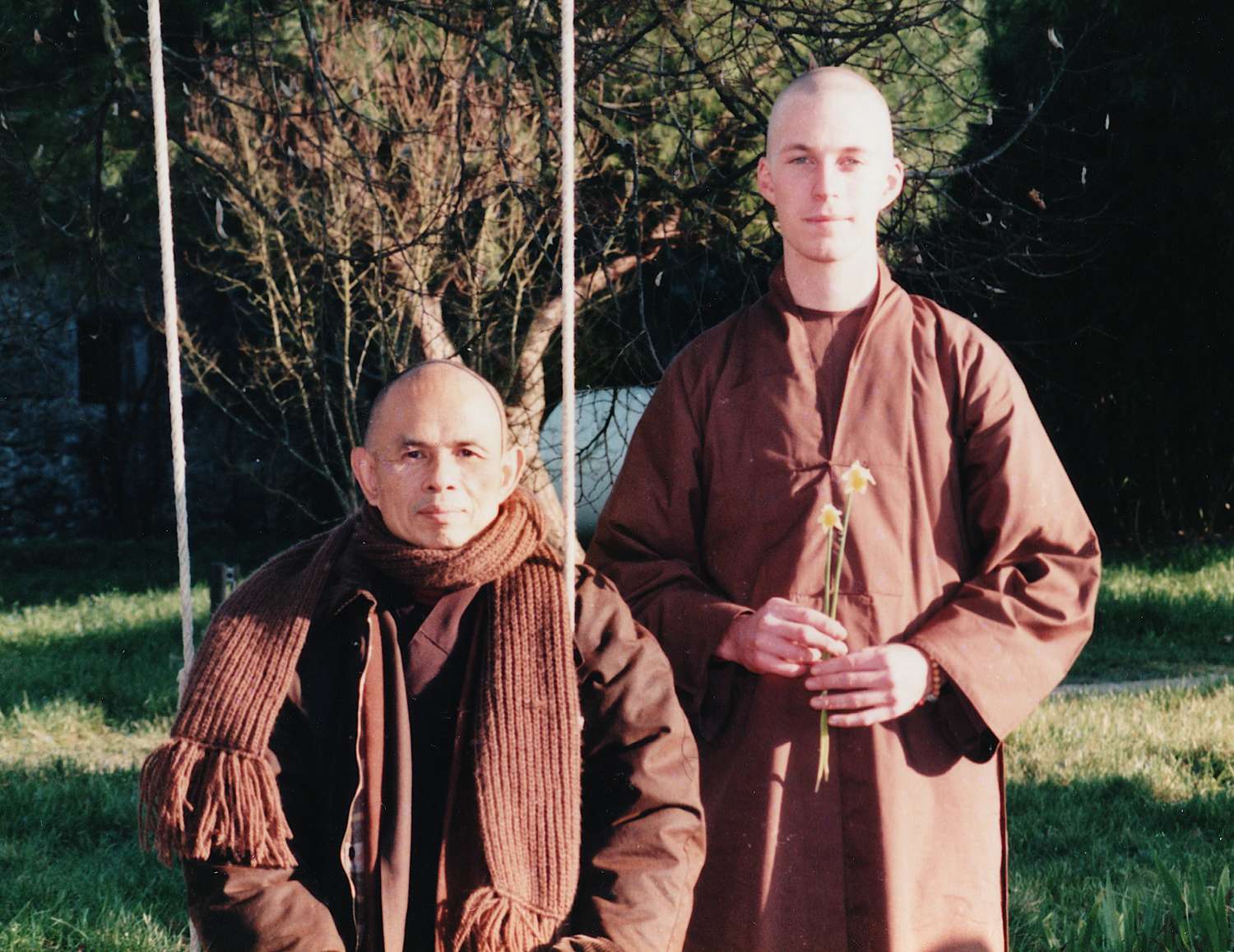

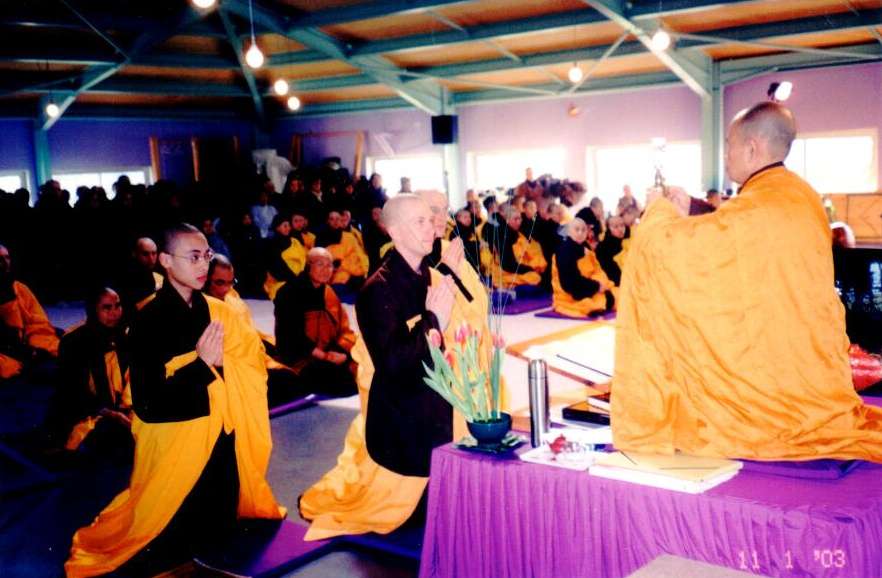

Brother Chan Phap Hai is an elder in the Plum Village tradition. In this interview excerpt from the budding Mountain Spring Monastery near Sydney, he shares with his younger monastic siblings his experiences, challenges, growing insights and lifesavers through 25 years of living in the Dharma and the sangha.

The spirit of experimentation in the early days of Plum Village

When I first arrived in 1996 I was touched by the joy and enthusiasm that everybody had, even with the very simple conditions at the time. For example, when travelling from Upper Hamlet to New Hamlet, we did not have enough transport, so many of us would sit on the floor in the back of the shopping van, on blankets.

When I ordained as a novice, the community was small – around fifteen brothers – and the majority of us were of a similar age, so we had a lot of energy. I remember when we planted the trees and dug out the lotus pond in the middle of Upper Hamlet, Br. Phap Ung and Br. Phap Hien (Michael C.) ran jumping into the pond in their short robes, playing in the mud. There were many simple joys like that. Many trees that now provide shade around Upper Hamlet were planted as small saplings by the brothers on their ordination anniversaries. Going through everything together in such a small sangha fostered a sense of closeness.

We did not yet have a designated monks’ building. The current one was built in 2002. We used to live in the Stone and Bamboo buildings, the Turtle Lodge and Dharma Breeze Hut, as well as in the rooms behind the kitchen. During large retreats like the Summer Retreat, the brothers would move out to tents, or consolidate in a few rooms, and some of our sisters as well as the guests would move into our rooms.

Being a small and young sangha, there was a lot less organisation, which gave room for a certain amount of experimentation to try different practices. For example, the practice of Shining Light did not exist in its current form for the first few years that I was in Plum Village. Before we began this practice, in the ceremony to close the Winter Rains’ Retreat we would make a formal request, “If you have seen, heard, or suspected something about my practice, please share with us.” Then the elder, usually Br. Giac Thanh, replied, “You’ve all practised well, but you could do better next year. Please touch the earth three times.” After a couple of years Thay began to give teachings about how we should renew this practice and not just do it as a form. The first few Shining Light sessions we had were a little intense, because we had not yet understood deeply how to engage with this practice. Of course, we are still learning, even after twenty years. At the time, we also didn’t need to be present, in which case we just received a letter. We quickly discovered that the Shining Light practice was more effective and strengthening for the person and for the sangha as a whole if we were present.

Other practices have disappeared, like fast walking meditation. One time, Thay said to us, “If you don’t sweat once a day, you are not my disciple.” Thay wanted to encourage everyone to exercise and to jog once a day. After one of our trips to China, Thay proposed that the sangha incorporate fast walking meditation into our practice schedule. So Br. Phap Niem and Br. Phap Do bulldozed a path around the linden tree in Upper Hamlet, put down some white gravel, and Thay suggested that we would do fast walking Chinese style before sitting meditation in the morning. We began this practice in the winter. As everyone knows, the winter in France is usually wet and cold. So often the back of our robes would be wet and white with flecks of mud from the wet gravel.

At one point, Thay suggested for every hamlet to have a scale at the end of the table to weigh our food. We would serve our food, weigh our bowl, and take note of how much we took. One time Thay noticed I was not doing it and Thay said to me, “Br. Phap Hai, you need to be like a river, not like a drop of water.” I replied, “Thay, a kilo of potatoes is very different from a kilo of lettuce.” Thay replied, “You think too much, Br. Phap Hai.”

Not feeling ready is a gift

We did not have all the classes and the structure that we have today. We learned mostly by observing and doing. Classes are wonderful, important and needed. At the same time the greatest learning we can ever have is in our everyday life. We do not discover the heart of the Dharma through books or classes. Those are about the Dharma, but they are not the Dharma. This is the difference between Dharma as lists, techniques, and concepts, and Dharma as a lived reality.

When I was a novice, we were lucky enough to have a Fine Manners class with Br. Giac Thanh, who offered what I think is the most important advice that I ever got in my monastic life, “What I want to share with you most of all is: don’t cover your monastic life with a whole lot of bells and incense.” What a beautiful encouragement for us not to hide behind anything, but to bring ourselves fully to our practice and to offer what we have, even if we think it is not much.

Today I hear some of the young ones say, “I’m not ready.” Honestly, after twenty-five years, I really still do not feel ready. Even now, giving a Dharma talk, I always feel like I have nothing much of value to share. Maybe if I felt ready, there would be a problem. Not feeling ready is a gift. We just show up in the best way we can and offer what we have. Nobody ever gave me classes on how to give a Dharma talk. I just learned by doing.

Thay also had different emphases from time to time. At one time he would ask us to give spontaneous teachings. In the middle of walking meditation or another activity, he might ask, “Sr. Kinh Nghiem, offer us a sutra,” and the person would then need to share an invitation to practise from a place of aliveness and spontaneity. There was no time to prepare, we just had to do it. It was nerve-wracking, but also a lot of fun.

Strong medicine from Thay

When I was a young monk, I suffered a lot. One time, I shared with Thay a very deep pain that I was carrying. Thay drank his tea, looked out the window and then he coughed. As he was coughing, I thought, Uh oh. (When he used to cough like that, we knew that we were going to get the hammer.) Thay put down his cup, turned to me and said, “Novice Phap Hai, why did you come to Thay and ask questions that you already know the answers to? Go and do it!” That is all the teaching I got! So I stood up, bowed, and walked out. I had hoped Thay would say something like “There there, poor you,” etc., therefore I felt a bit angry with Thay. As I came out of Thay’s room, as a twenty-two year old, I remember kicking the gravel around the driveway in New Hamlet. For about two Dharma talks whenever Thay caught my eye, he would smile lightly. I am ashamed to tell you that it actually took me a couple of weeks to realise what Thay had offered me. Thay would always point to the capacity in you and water your confidence in your own ability to transform. The reality was, I did know exactly what I needed to do. I just didn’t want to do it. Thay knew this and offered what I needed most in that moment and in my life of practice: confidence in my capacity to be able to understand and resolve issues myself. That was the strongest and most precious teaching I ever received from my teacher and I am deeply grateful. That was when Thay really became my teacher, not just a faraway figure that I would listen to at a Dharma talk or attend, without any real relationship.

Whilst others can help and support us, ultimately, as practitioners, we ourselves need to be able to look deeply and understand our situation to be able to really transform our suffering. Thay gave us those tools.

Big challenges in the early days

One of the challenges I faced growing up in the sangha was learning how to ask for and receive support. I came from a family environment in which I had to be very responsible in order to survive, so I had a tendency to be a bit too responsible and not want to communicate what was really going on inside. I also did not know how to take advantage of the presence of my elder brothers or sisters. The sangha’s Shining Light and guidance helped me to realise that my real contribution and real transformation was not in volunteering for many things, but something else entirely. I had to learn to be one element of the sangha rather than taking over, even if I thought I was helping. This is a bit like the difference between being a soloist and playing in a band. Of course, this is a lifetime’s journey and I still have a lot to learn in this area.

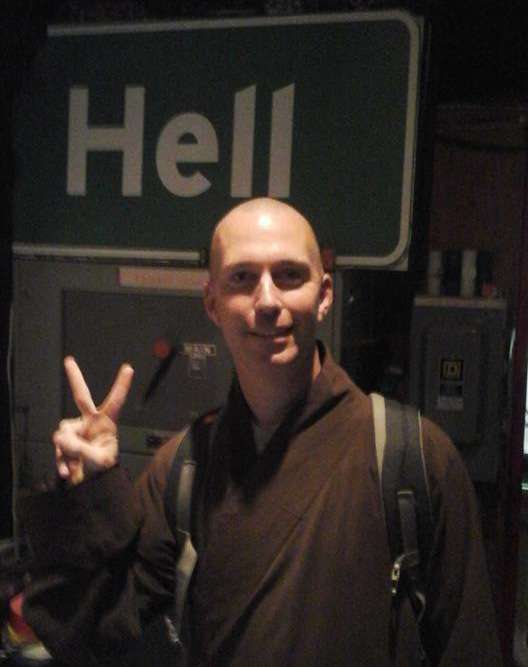

Another challenge was my distinctly direct Australian communication style. Australians show respect and closeness to those we care about by being very direct, and have a self- and other-deprecating sense of humour. This comes from the background of the difficult environment of Australia–droughts, floods, fires–needing to make light of it and to come together as a collective. For example, last year a flood washed out both roads into and out of this mountain, leaving us cut off from supplies for ten days. The local people began joking around, downplaying it, “Oh, it’s a bit bloody wet, hey mate?!” I had that tendency coming to Plum Village. If somebody was too serious or emotional about something, I would respond in this way. For many other cultures, this feels rude, which meant I had a lot of Beginning Anews. I needed to learn and adapt. Coming back to Australia I had to go through reverse culture shock.

Lifesavers

The biggest lifesaver of my monastic life is something that many do not enjoy at all, and that is my Shining Light letters. A few years ago I went through a situation where my whole world fell apart and for a brief moment I felt that the world or the sangha would be a better place without me in it. It was very difficult to see any good qualities in myself. I think we all have these moments. In that challenging moment, I reached for my Shining Light letters. I have accumulated a lot over the past quarter of a century. I read each of them and saw how clearly the sangha as a whole saw me. Not only did the sangha accept me, but actually loved me for who I am. In reading those letters, I felt as if the sangha was saying to me, “We see you, we see the Dharma you are meant to bring, and you are important to us.” Being seen and feeling this deep connection is something very precious. It honestly saved my life. I recommend that you do it.

Twenty years ago I had a dream in which Thay came up behind me, put his two hands on my shoulders and said, “Br. Phap Hai, is it Yes or is it No?” In the dream I turned to Thay and said, “It is Yes, Thay.” That dream has always remained with me. Whenever I go through a difficult moment, this is the other lifesaver I have: the practice to say “Yes” to whatever the situation is and have the mindset of “I am here and available. I will do what I can.”

Tapping into the insight of Thay

A few years ago in a monastic retreat in Magnolia Grove, a couple of us were having tea together. In that conversation, we were discussing, “What do you feel Thay asked you to do or what was the invitation that Thay offered to you?” It was a very beautiful conversation. Reflecting on it, I felt that Thay transmitted something unique to each of us. When we come together, there is a beautiful flowering. What Thay shared with me was, “If you’re doing the same thing in twenty years, you will have failed.” I hold that. Of course, Thay was not talking about the outer forms of the practice but how I, for example, relate to my brothers and sisters or to practices such as mindfulness of breathing. It was an invitation to go a little bit more deeply and to not be afraid of unpacking the riches that Thay has already offered us.

Over the years when our community offers teachings, I have witnessed people being blown away by teachings that often seem quite ordinary to us but are rarely taught in other lineages. Thay is an extraordinary teacher and has offered us so much in an incredibly condensed form, in the talks on Thursdays and Sundays and through his way of life. For example, while I was giving a weekend retreat on the Four Nutriments, a very well-known Theravadin sutra scholar and teacher approached me, saying: “Did Thich Nhat Hanh teach this in Plum Village? We only teach this in the context of quite focused meditation retreats for advanced practitioners.” In Plum Village of course, we consider it one of the most essential teachings of the Buddha and Thay offered us many teachings on the Four Nutriments. I really feel that our job as practitioners and Dharma teachers is to unpack these riches, to keep exploring and developing them and offering them to the world.

The role of elders

I ordained when I was twenty-one years old and this year I turned forty-six. There are young monastics who were born after I had already become a monk. Wow! From being a young community in physical and Dharma age, our community is now beginning to consider what it means to be an elder. I like to ask myself, “What does it mean to be a resource, to take care, to hold space and not dominate, to not get caught up in so much administration but to really try to listen and care for the young ones?” I think of our role as elders much like being the banks of the river, helping to support the flow of the river and trying not to block it. While we support the flow of the river, we are also being shaped by it.

What I really want to share with you is that even though we may have different ways of showing it, all your elders care deeply for the young ones and want to offer you the best conditions we can.

Developing spiritual friendships

A while back I had the chance to mentor aspirants and young novices at Deer Park Monastery in the U.S.. They asked me for some advice on how to connect with the elders since sometimes they felt a bit distant. If we see the sangha as a garden, like Thay shared in the book Joyfully Together, then as a young monastic the most wonderful thing we can do is walk under the shade of these tall trees who are our elders and rest against their trunk. Soon enough, you will also have younger brothers and sisters to whom you will be offering support and care and guidance.

Good friendship in Buddhism means more than just associating with people that share our interests or have similar outlooks. It means actively seeking out companions to whom we can look for guidance and instruction.

A good mentor or elder from time to time will hopefully share things that we disagree with or we see differently, and in those moments we should know that we have indeed met a good and kind friend, since they will help us to grow in some way.

Our relationship with each other as elders and juniors is very much a reciprocal one. I encourage each of you to actively build spiritual friendships with your elders, taking every opportunity to naturally approach them, drink tea and connect with them, especially if they are different from you. You will then discover many amazing things about them. They will offer you many deep gifts. Most of all, if you build a Dharma friendship with them, you will discover that they are human. That will give you confidence in your Dharma because you will see the unique nature of the Dharma body and Dharma expression of each one–and then, most importantly, you will begin to see it in yourself.

So please, do not underestimate the importance of this relationship between elders and juniors. Do not take this special gift for granted. It is one of the most precious transmissions of monastic culture. If we cultivate it properly by allowing ourselves to be challenged and supported by the sangha, welcoming confusion and doubt, joy, vulnerability, confidence, and guidance, then we will generate within ourselves all of the tools we need in order to go very far on the path. If you find yourself too busy in work or planning for retreats, those are the times that you should find time to hang out with your mentor or elders. Please make time in your day, and space in your mind to do so.

May these simple words from the heart of your elder brother be of use to you on your path both now and for a long time in the future. Please treasure every moment of the sangha just as it is right now. In a few years you will look back with much fondness on this time and understand it for the gift that it is.