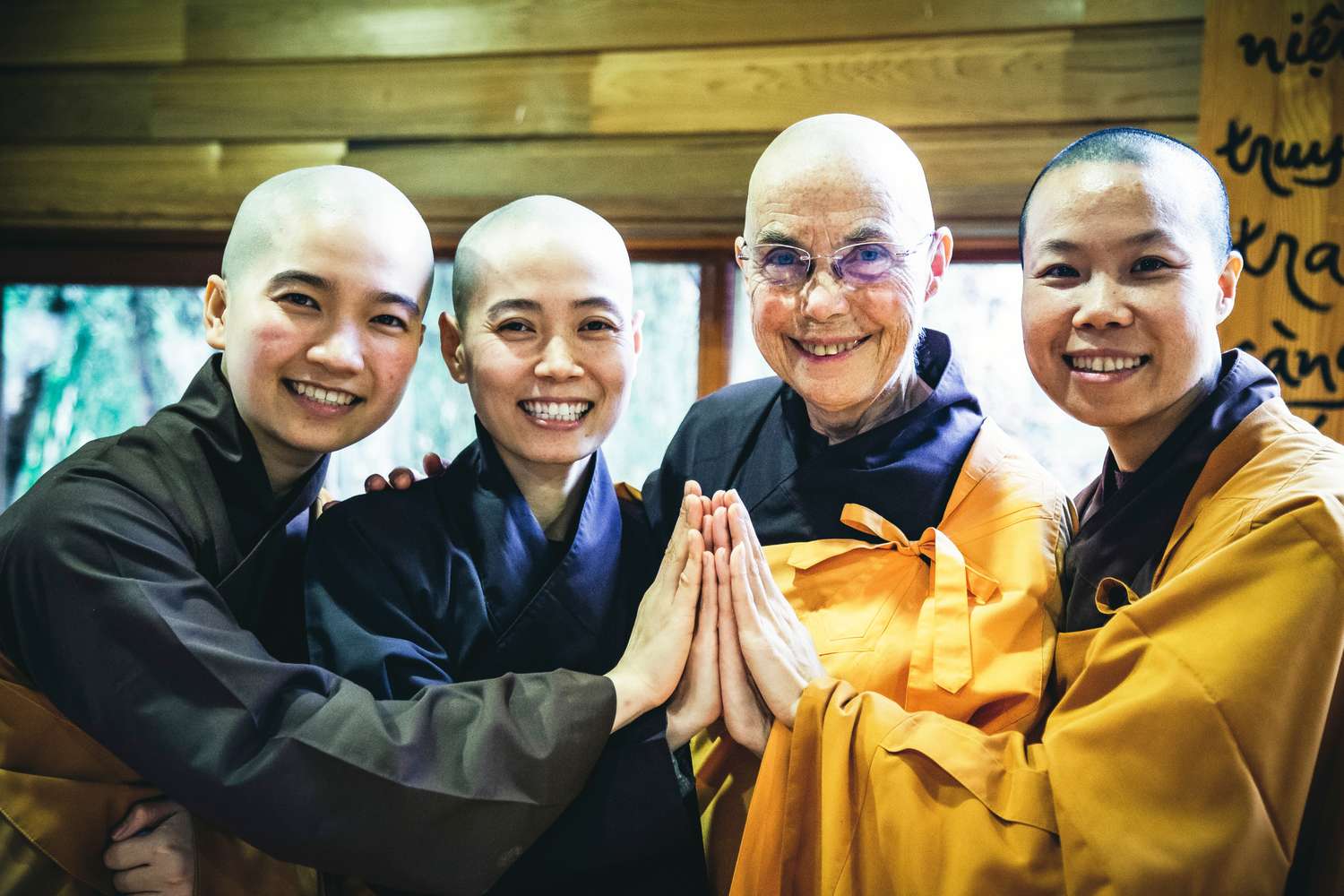

Sister Chân Diệu Nghiêm (Jina) & Sister Chân Từ Nghiêm (Eleni)

Sister Dieu Nghiem (also known as Sr. Jina) arrived in Plum Village in 1990. She ordained as a monastic in Japan in the Soto Zen tradition. Sr. Jina was the abbess of Lower Hamlet from 1998 to 2014. Sister Tu Nghiem (also known as Sr. Eleni) first came from America as a lay friend in 1990 and ordained in 1991. We asked our beloved elders to share some of their memories of the early days of Plum Village with us, and about the beginnings of the Plum Village basic practices, and their lives in the fledgling community.

Life in community

Sr. Tu Nghiem: It was such an eye-opening experience for me (to live in a Vietnamese community in rural France), coming from Manhattan–a city with big concrete apartment buildings. It was a totally different experience, and I appreciated so much the way the Vietnamese mothers and fathers, the children, were happy and harmonious together.

My parents were both children of immigrants, so they had the experience of speaking their parents’ native language and learning English later on, so maybe they transmitted to me a sense of feeling comfortable with other cultures. I was used to this double culture. The adjustments were not so difficult, and the Vietnamese culture I found was gentle and very respectful. I remember how Thay greeted the father of Br. Phap Ung. Thay stood up from the table, and when (Br. Phap Ung’s) father came into the room, Thay went up to him, (as he was older than Thay in age), and greeted him in the appropriate way. I was just so touched by Thay continuing to keep the value of addressing the parents of his disciples in a respectful way.

Thay always loved to hear Vietnamese songs, so after a Dharma talk or before walking meditation he’d invite one of the brothers or sisters to come up and sing. Another time for singing together was after our meals. There were just two long tables where the whole sangha sat. Thay was at the head, Sr. Chan Khong next to him, and then the attendants. We ate our meal mindfully in silence, and then after the meal, it was time for singing and the plates were left on the table. It was really relaxed. Thay really encouraged music and singing as part of our monastic life.

As I look at the name Plum Village, I see it was truly a village. When I had the opportunity to go to Vietnam, I recognized that this is what a village is. Thay brought this way of living, the feeling of family, this spirit, to Plum Village. We called each other Su Chi (older sister) and Su Em (younger sister/brother) and Su Ong (father).

Sr. Jina: When I just arrived in Plum Village, everything seemed to be more or less organised. When there was working meditation there was a gathering and they said, “Oh the toilets need to be cleaned, who wants to clean the toilets? Yes, I’ll clean the toilets! The meditation hall needs to be set up…Yes!” Everybody just volunteered to do the work. I didn’t mind that it was not organised in every detail, I thought it was very nice to have this organic kind of feeling.

One of the things in Plum Village that I really appreciate is that whenever there is something to celebrate, we celebrate it. Even if we’ve never heard of that celebration before, but you have, you tell us what it is about and how we do it and we’ll do it. So I hope that we keep this Plum Village tradition. Thay was really encouraging of that. Celebrate life! That’s why we have the Daffodil Festival, Plum Blossom Festival, Full Moon Festival, all those things.

The teacher-student relationship

Sr. Tu Nghiem: In the early days we were all beginners in the practice, brand new, one year to two years old. There was no mentoring. Thay had his room in Lower Hamlet and he would call people into his room. His attendant would say, “Thay wants to see you,” and you’d go into his room. So that’s how he would train us.

In those days he was training the abbess and abbot. They were called into Thay’s room, and the rest of us were left with freedom. Some were being trained to be his attendant, so they went into his room and learned to prepare tea. I have so much respect for Thay starting a monastic sangha with beginners. We were practically lay people, and Thay was teaching us how to be attendants, how to be abbots and abbesses. When Thay would learn about the difficulties in the sangha, he would give the next Dharma talk based on those difficulties.

I was accepted, and for me that was enough. In the year 2001, I was able to be Thay’s attendant for one day at Deer Park Monastery (in the United States). The experience was so funny! “You can be Thay’s attendant this evening,” they told me. I had no training so they told me what to do carry Thay’s bag, where to place his shoes in the meditation hall, etc. While attending Thay I left my shoes there in the mudroom during the Dharma talk, but when it ended, Thay left by the opposite door. Thay left in his slippers, and I had to follow Thay in my bare feet! And then I think the brothers and sisters came to rescue me.

Sr. Jina: I was very impressed by the calmness that Thay radiated. He was not in any way affected by whatever was happening around him. In the 21-Day Retreat it was all very organised and the Summer Retreat was very organic and Thay moved so naturally through both. I thought, this is very beautiful to see, in the midst of a very lively group of people, there was Thay, so naturally moving around, happy. So my first impression was of his stability and clarity.

Dharma talks

Sr. Tu Nghiem: What is now the Lower Hamlet dining room was very small back then. Thay would come in and give the Dharma talk. In the back of this room there was a ceramic divider, not completely to the ceiling but halfway, like a little wall, and then ceramic tiles. Behind this were stove burners to cook! So towards the end of Thay’s Dharma talk we would sniff, sniff, smell that the sisters had started to cook. What was so beautiful about Thay in those days and our simple lives was that it was natural.

We already had the chiming clock in the dining hall. It would chime every fifteen minutes. Thay would stop, we’d all breathe, and it was very peaceful. Then Thay would continue with the Dharma talk. In those days it was Br. Nguyen Hai who was the cameraman. It’s amazing how they’ve preserved these early teachings. In those days Thay used a cassette recorder, and they’d have to stop and put in a new cassette and continue.

Sr. Jina: Thay’s teachings were very clear. With certain teachings that one can say in a particular way, Thay just said, “This is it.” We listened to Thay, we tried to understand and even if we didn’t understand, it was just being in Thay’s presence. That was enough and I had already been so nourished by the 21 Day Retreat (after my arrival) I thought, I have at least three years material (to practice with).

(When the talks were in Vietnamese), Sr. Chan Khong used to translate and I enjoyed listening to Sr. Chan Khong very much because you also get side information, then you have a better context! It was very alive, I really enjoyed that.

In the 21 Day Retreat and the Summer Retreat, Thay was addressing a lot of issues that were happening in the sangha, like in the lay sangha, family issues, and also from the questions of the retreatants. During my first Winter Retreat, I thought, oh now we really hear the scholar speaking, and that’s also what I was looking for. In the winter it was really study time.

Care packages for Vietnam

Sr. Tu Nghiem: We wrapped care packages to send to Vietnam during the early days of the Hungry Children’s Program, in the early 1990s. We would go to the pharmacy and buy over-the-counter medicines like paracetamol or Tylenol, general medicines that did not need a prescription. We put them into little boxes with a letter. The letter would be written in a way like someone from Plum Village was writing to a friend in Vietnam. Our identity was never revealed because in those days you could not provide information to the government that it was coming from Thich Nhat Hanh or Plum Village. So these little care packages contained a beautiful letter, saying, “I hope your family is well,” encouraging them to be creative and to receive the gift that we, as their friend, were offering. Now I learned that they would sell the medicines on the black market to buy rice. The care packages were sent very often, maybe every week. It was such an important part of the early history of Plum Village engaged Buddhism – to help Vietnam after the war, because there was a lot of poverty.

Christmas

Sr. Tu Nghiem: At Christmas we would go to the Hermitage and gather in Thay’s library. There was a little Christmas tree on Thay’s table, and underneath there were a couple of packages. When Thay received Christmas presents, he would open them very mindfully, and if it was a box of cookies or dried fruit, Thay would always share it with us. This was his practice, that he shared with the sangha. That really moved me, how he wanted to have all his children enjoy his gift.

Sometimes we were allowed to bring food to Thay on a tray. And once I remember Thay was cooking scrambled tofu for us. You know, it was so wonderful to see Thay cooking. He had on his winter sweater, a thick woollen sweater from Denmark, and he would be there at the stove cooking for all of us. It was so wonderful, so very caring for his disciples. I sat there in silence because I never knew what to say. At the table, Thay would share his food, and the plates were so small, just two, three pieces of tofu. He would take one and then share it with everyone. I thought, how can he survive, taking such little food?

Evolution of the basic Plum Village practices–Tea meditation

Sr. Tu Nghiem: In 1990-91, we lived in Lower Hamlet. Every Sunday afternoon, there would be a tea meditation (for everyone, lay and monastic) in the Red Candle Meditation Hall. Thay and Sr. Chan Khong would come sometimes, and during the years when Br. Giac Thanh was in Upper Hamlet, he would come and be the tea master. It was a very zen experience. Br. Giac Thanh would bring poems from the Vietnamese poets. It was a time for sharing poetry, a very creative time, very relaxed.

Br. Giac Thanh was, I believe, the master of relaxation. He spoke very slowly and gently. He read poetry with a lot of feeling and meaning, and then he would translate it into English if it was a Vietnamese poem. There was an opportunity to share songs. In those days we sang Vietnamese songs from the collection of Vietnamese songs in the book. There was also sharing about how we were doing.

Continuing our teacher and reinventing the practice

Sr. Tu Nghiem: Something I valued so much in Thay and I want to continue is the path of the Bodhisattva Sadaparibhuta, which is always finding the best in people and letting them know they have these good qualities. Thay always believed in this. He once mentioned a sutra from the Buddha that says if someone has only one eye, you protect that one eye. That means the practitioner is weak but still has an aspiration. Protect that aspiration – don’t be so harsh. Thay always had so much compassion. His understanding was immense.

People came with so-called mental illnesses and Thay would say let them stay and practice. No pressure was put on them. We just asked them to come to sitting if they could, or walking meditation, and eat with us. And they would stay around a week. I remember Thay said the collective energy of mindfulness, compassion, and kindness, and the culture of gentleness would help that person. That was Thay’s way in the early days of letting the sangha be a village where everyone could come and be here. I remember Thay’s qualities of deep looking, great compassion and understanding, and always looking for the best in people, giving them a chance.

Now we have also become a training center for monastics. We’ve become the Institute of Higher Buddhist Studies and we are in a digital world. But I think it’s good to maintain the values of early Vietnam, the culture, the food, the poetry, the Lunar New Year celebrations. There are brothers and sisters also interested in neuroscience, deep ecology, and that’s Thay’s Engaged Buddhism. I think all of it can be part of Plum Village.

Sr. Jina: Thay was always reinventing, renewing. Are we also renewing? Is there any practice that we think could be renewed? There may be some kind of practices that have lost their shine a little bit.

Thay was always practicing walking meditation, from the very beginning, even before there was a sangha. (I remember one day) I was attending Thay, in the sense that if Thay needed anything I would do it, Thay didn’t have an attendant as such. I would walk behind Thay from the meditation hall in the Upper Hamlet to Thay’s hut to see if Thay needed anything, and Thay said something to me as we were walking and I just kept quiet. It was not a question but I didn’t give a counter remark or start a conversation or continue the conversation because I was walking and I thought well, we’re walking, why should I say something? And Thay stopped and said, “Do you want to stop while we’re talking?”, “Yes, Thay.” So we walked and then we talked in the hut, and from then on when you walked, you walked, when you wanted to talk, you stopped. That was a new practice that came in.

Keeping the essence of Plum Village

Sr. Tu Nghiem: I think there are several levels and aspects to this. Thay wanted to create a monastic sangha, and an international fourfold sangha. So I think this is so important for the future of Plum Village, to keep the balance, that it remain international and fourfold – that means the nuns and laywomen and the monks and laymen are all part of the Plum Village community.

The essence of Plum Village is to continue to share the practices of mindfulness in as simple a form as possible, to meet the needs of people around the world, of different cultures, of different religions, and to present it in a way that’s understandable and acceptable by people anywhere. We keep the simplicity of the teachings, the basic teachings of the Four Noble Truths and the Eightfold Path, and keep them accessible to beginners in the practice.

Also, we keep our tradition, we don’t dilute it. We keep the Vietnamese heritage, the lineage, the culture, to learn from. We want to learn from the beauty of Vietnamese culture, its gentleness, friendliness, and acceptance of newcomers. That’s what impressed me in the early days, the beauty of the flower arrangements, the tea meditations. And the Western bands, the monastics with their drums, their electric guitars, we can have all that. I think it’s important because it reflects the world now.