Sister Chân Đoan Nghiêm

Dear sister, when you first came to Plum Village, what left the strongest impression on you?

Poor and desolate! My family had known about Plum Village for a long time and often described it to me, so I already had some ideas about it. When I first came to Plum Village in the winter of 1989, all I saw were simple stone and brick houses and some unfinished buildings. Looking around, everything was so plain, not at all what I had expected. I was a little surprised to see how poor Plum Village was. The Dharma Nectar Hall (of Lower Hamlet) only had a roof and steel frames, without walls. A building with bare stone walls served as the dining room. This was also the room where Thay gave his Dharma talks and a storage for firewood. When it rained, we had to use pots and basins to catch the water from the leaks.

So what has made you stay till now?

It is because I truly want to walk this path. In the beginning, I came to Plum Village out of curiosity. My sisters and nieces talked a lot about Plum Village, so I wanted to find out for myself. When I saw people attending the schedule, I just followed them. I didn’t really want to learn anything yet. Fortunately that year, Thay was writing Old Path, White Clouds and teaching on it in the Winter Retreat. I felt like Thay was recounting stories about the Buddha and his disciples as well as their way of life. I really liked it. The stories showed me that there was a way of life different from the conventional one that I knew. In fact, I did not know what I wanted then. There was nothing in society that touched me or appealed to me. I was always brooding and did not see a way out.

Then I heard the teaching on the blind turtle. This was the essential key for my decision to ordain as a monastic. In that teaching, the Buddha taught that it is very difficult to have the chance to be born a human, more so to encounter the Dharma, and even more so to become a monastic, and even rarer to become enlightened.

While listening, I ticked off the difficult parts that I had already gone through and I saw that I had not yet done the part about becoming a monastic. So I decided to ordain, because I didn’t want to be a blind turtle taking hundreds of years to be lucky enough to poke its head through a hole in a piece of wood floating on the ocean surface. I wanted to give monastic life a try. Since I did not know anything about spiritual life and really wanted to explore it, whatever Thay taught, I followed to the letter. For example, I learned the gatha about sweeping the floor by heart and recited it out loud when I swept the floor. For each line, I made one sweep–totally concentrated! I took Thay’s words to heart because I felt I was a “newbie” in this way of life.

When you were Thay’s attendant, did you have fun? Did Thay teach you how to be an attendant?

Thay didn’t teach me how to be an attendant. In 1990, right after my ordination, Thay went on a U.S. teaching tour. Before leaving, Thay gave me a copy of the Commentary on Trainings for Novices by Venerable Thich Hanh Tru. Thay really treasured this old, yellowing book. He said that he himself used this very book to practise as a new novice. Hearing that, I also treasured the book. I bought some transparent sticky plastic to cover the already frayed and torn book. However, though I read the commentary, I didn’t pay much attention to its teachings. It wasn’t until the end of 1992 that I had a chance to attend Thay for the first time.

That day, the snow was very thick on the road, so we were unable to drive. After the meal to say farewell to the old year, Thay had to stay back in Lower Hamlet in the “Hoa Cau” room (Areca Palm Flowers). The sisters told me to attend Thay. I hurried to take care of the firewood to warm up the room. When that was done, I went back to my room and began to flip through the novice trainings commentary. By that stage, how could anyone possibly sit down and memorize a chapter on “Attending Your Teacher”?!

I sat with that chapter almost the whole night. I had a lot of “concerns,” because the book said that we “should not go to sleep before our teacher and should rise before our teacher.” That alone was enough to make me panic! I wondered, What time does Thay go to sleep? What time does he rise? Questions kept popping up as I read paragraph after paragraph. So that night, I didn’t dare to go to sleep before Thay. I had to run past his room to see if the lights were off before I dared to go to bed. My room was in the Red Candle Building while Thay’s was in the Purple Cloud Building. That night, despite the newly laid thick layers of snow, I kept going back and forth checking for the lights in Thay’s room. In summary, I did not sleep for almost the whole night. I stayed up, memorizing the steps on taking care of one’s teacher–whatever the book said, I would do just the same.

I didn’t know what time Thay would rise the next morning. I thought that Thay was a Zen master, so for sure he would rise as early as the masters in the Zen stories I often read about. At three in the morning, I ran over to his room. I walked on tippy toes, and “tapped lightly with nails” on the door instead of knocking because in the commentary it said to “tap lightly with your nails,” so that was exactly what I did! But how could Thay hear a sound that was even quieter than a mosquito buzzing around his ears? How could the sound of fingernails tapping penetrate the thick stone wall and the wooden door? As I did not hear Thay’s response, I had to give up and go back to my room.

So I kept running back and forth between the two buildings from three until eight in the morning! By that time, I was out of patience! I didn’t bother to tap with my fingernails any more, instead, I used my fingertips to knock on the door. Still, I did not hear any response from Thay. I started to knock harder–nothing from Thay.

I was so nervous–had something happened to Thay? In the commentary, it said that we shouldn’t go into our teacher’s room without being invited. I was beside myself. I looked through the keyhole to see if there was any light. If there was light, that meant Thay was up. Yet through the keyhole, I only saw darkness. Luckily back then, all of Thay’s students wore wooden clogs. At first I went barefoot as I was afraid of disturbing Thay. But by then I had put the clogs back on and clop-clopped to his door. As soon as I knocked lightly on the door, I heard Thay’s voice, “Come in.” Thank Goodness! How happy I was!

In my head I already had a list of what needed to be done that I had learned from the Commentary on Trainings for Novices. Upon entering Thay’s room, I gently closed the door and scanned the room. Thay was still in bed, listening to the morning news (Thay told me this), so I couldn’t make his bed. My eyes went around the room to see if there was a chamber pot, which was also mentioned in the book. I followed the book exactly and completely forgot that Thay’s room had a toilet next to it, so why would he need a chamber pot? Not seeing a chamber pot, I turned to the wooden stove, fed it some firewood, then boiled water for Thay to soak his feet.

I was so absorbed in carrying out “the list of things to do while attending Thay” that I didn’t pay any attention to Thay. Suddenly I heard some movement behind me, I turned and saw that Thay was standing up. As soon as Thay stood up, I jumped over to fold his blanket. Then I put up his hammock because Thay liked lying in the hammock in his room. After brushing his teeth, Thay lay down in the hammock. I turned to make tea, then brought a hot water basin for Thay so he could soak his feet while sipping tea. When there was nothing else to do, I came around to sit by Thay’s hammock and waited to see what he would tell me to do next. The very first thing Thay said to me was, “When I have some time, I will teach you how to be an attendant.”

However, in the end, Thay did not teach me how to be an attendant. I think he said it at the time because he saw that I was making too much of a fuss.

Back then, I was very naive! After each Winter Retreat, Thay took his monastic children to visit a snowy mountain. According to the novice training commentary, “Attending your teacher, when crossing a river or a waterway, you must find out where it is deep and where it is shallow in order to make sure that your teacher can cross it safely.” But there was no waterway or river there, only snow. From time to time you can miss your footing in the snow. I thought that Thay might slip so every time I saw some snow, I would overtake Thay so that I could check the path ahead for him. I kept walking in front of Thay and stamping at the snow to see how deep or shallow it was. Thay said, “Doan Nghiem, it’s ok, don’t worry my dear, I can walk.”

And that’s not all! Then there is the story about holding an umbrella for Thay.

The commentary says that while walking with our teacher, we should not step on their shadow. So while walking with Thay, I didn’t look at him, but only at his shadow to avoid stepping on it. Thay walked slowly. Often on the way out, his shadow was on one side, but on the way back, the sun and his shadow had gone to the other side. So following behind him, I also switched positions. From time to time Thay wanted to stop and talk to his attendant behind him. When he turned one way I was there; a moment later I had changed position, he turned and I wasn’t there anymore!

Looking back at my memories of those early days, when I first ordained, and of being an attendant, I feel very happy to see how simple my mind was. I completely let go of conventional ways of thinking. Whatever I was taught, I applied it. I never questioned Thay.

We have heard that in the early days, you had to do everything from chopping wood, driving a plough tractor, to fixing electrical problems because there were so few people. What was it like?

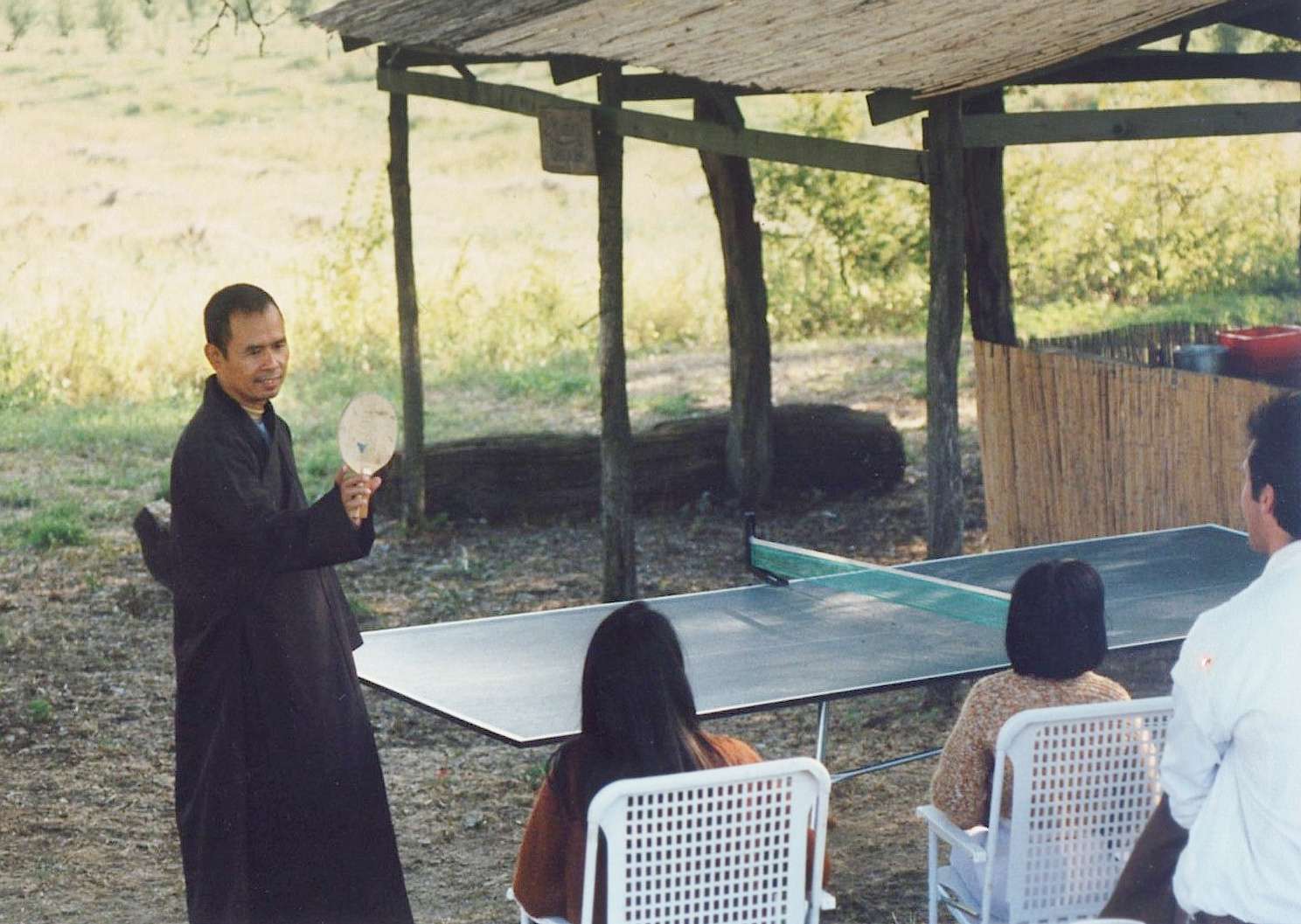

During my time the rotation team system was already in place, but there was only one person per team. It was really fun! In my first year as a novice, cooking in the Summer Retreat was my challenge. The sangha only had two or three sisters at the time and each had their own responsibilities. In the summer of 1990, we invited Aunty Tam (Sister Chan Khong’s elder blood sister) to come and cook and I was her “gofer.” There were only two of us cooking for the whole 30 days of the retreat. My job was cleaning and washing the pots in the kitchen, and chopping vegetables for Aunty Tam. I also covered the job of washing pots after the retreatants had finished serving their food. Back then, the only thing I knew how to cook was rice. There were only Vietnamese people in Lower Hamlet so there was rice for all three meals. It’s thanks to that Summer that I learned how to cook. When the retreat was over, we returned to our rotation. One person cooked per day. Everyday was a festival! In those days, Plum Village didn’t have many retreats like we do now. There was only the Summer Retreat and the Winter Retreat, organized when Thay was at home (and not while away on teaching tours).

When Thay went on teaching tours in the U.S. or around Europe, we listened to Thay’s talks from the Summer Retreat because during the summer, we all had to do mindful service and could not attend the Dharma talks. There were no videotapes yet, only cassette tapes. Activities were very simple. We had morning and evening sitting and chanting, like we do now. However, there were two sessions of sitting meditation interspersed with slow walking meditation in between. At the end of the second sitting, we sat down to chant the sutras. In the past, the Daily Chanting Book didn’t have as many chants as it does now.

Daily mindful service revolved around the plum orchard. We did everything from A to Z: trimming, fertilizing, and other chores. Just a handful of brothers and sisters did all the work; we didn’t hire anyone to help us. There were more than a thousand plum trees so we worked on them the whole year round. But it was a lot of fun because the whole “family” went out to the plum orchard and while working we talked and played together.

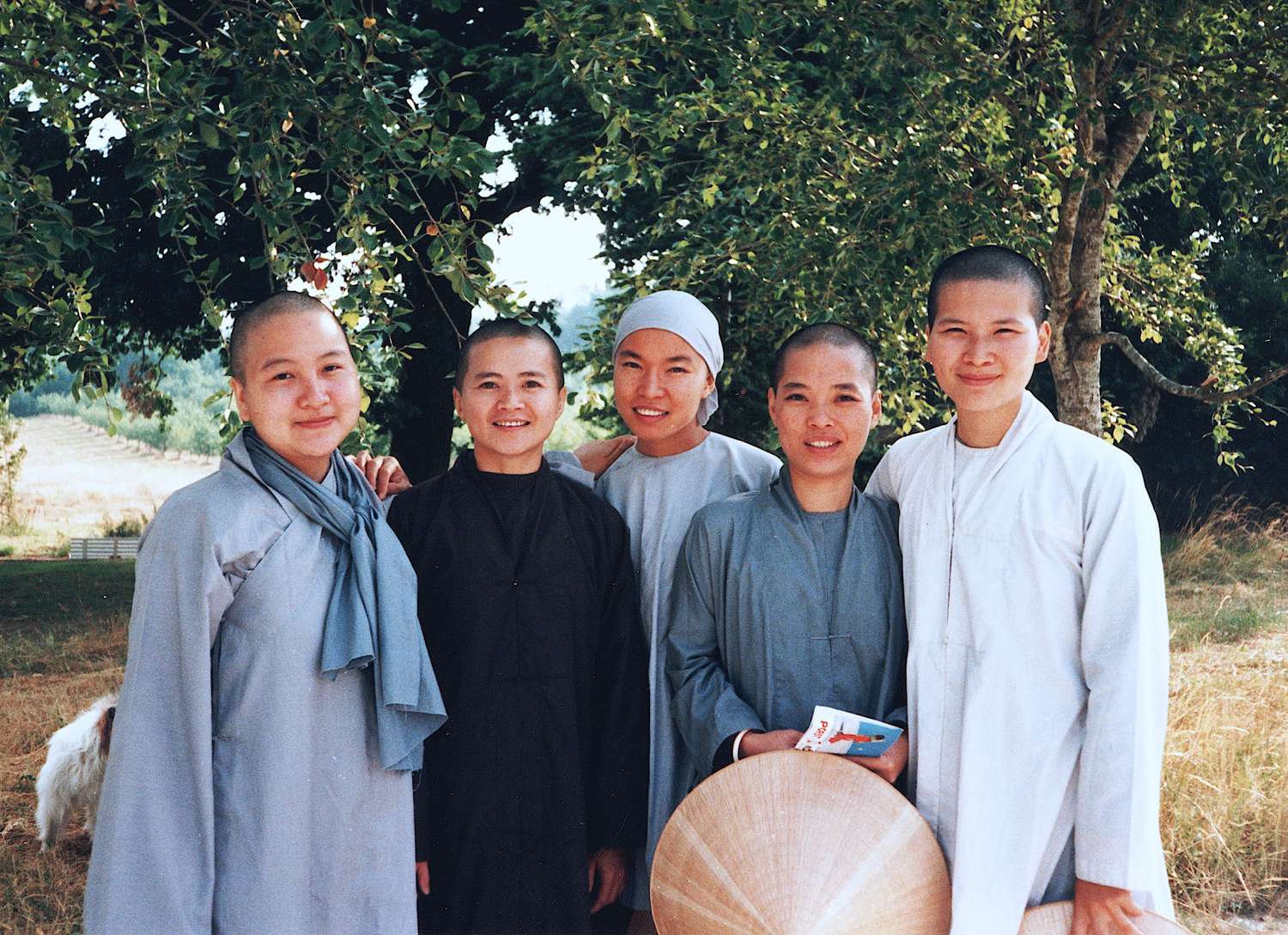

Back then, formal meals only happened in the summer. We had to wear our sanghati, but anyway it only happened once a summer. Life was simple back then with few activities. We didn’t listen to many Dharma talks, except during the three months Winter Retreat. It seemed like we played more.

In order to save expenses, Thay told me to give a hand to the masons to help repair the buildings. I learned how to lay bricks, pour concrete, and install all kinds of insulation in the ceiling… I didn’t know French so I did whatever the masons showed me to do. When it was time to pull the electrical lines into the Dharma Nectar Hall (in Lower Hamlet) or for the Sitting Still Hut (in Upper Hamlet), Br. Phap Lu (still called “Anh Hoang” then) and I did it together. We did almost everything ourselves. In winter, it was cold, so we collected discarded wood chips from sawmills to heat up our rooms and reserved the firewood we bought for Thay, the meditation hall, and the study room where we listened to Dharma talks.

The wood chips burned very fast and strong, but left no charcoal so at midnight our rooms were freezing and our blankets also went cold. It felt like we were warming up the blankets. I couldn’t bear getting out of bed in the morning. That was one of the reasons for my laziness going to sitting meditation. I don’t know who it was that reported it to Thay. When Thay came to Lower Hamlet, he told me quietly, “My dear, you can take your sleeping bag to sitting meditation and you can sleep in the meditation hall if you need to.” Back then, nobody took a sleeping bag to sitting meditation, but Thay allowed me to do it.

Can you please share with us about the teacher-student relationship between you and Thay and how Thay took care of you and taught you?

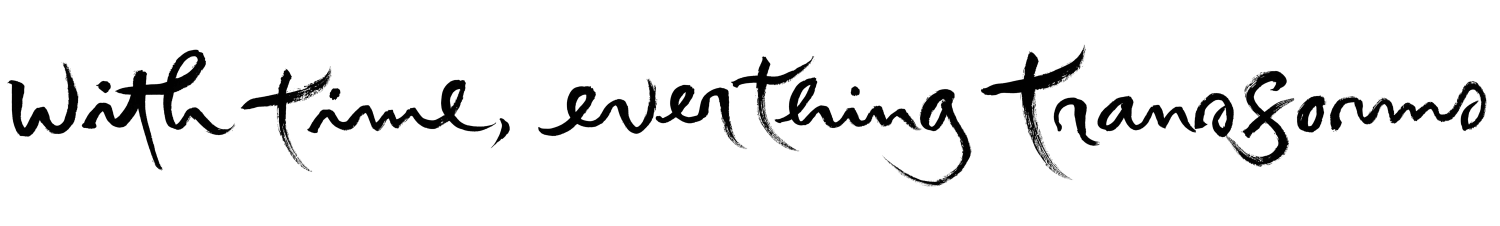

Thay took very good care of his monastic children. Thay really cared that I had ordained young and by myself and he was afraid that my mind would not be solid enough. Sr. Chan Tu, a sister who had ordained before me, had left just a few months after her ordination, so Thay was worried that I might leave as well. When Thay was not on teaching tours, he often came to Lower Hamlet to spend time and have a meal with us. We were only five sisters then: Sr. Chan Khong, Sr. Chan Duc, Sr. Chan Vi, Sr. Thanh Luong (who came from another temple) and myself. It was very nice that Thay sat with us to eat. Sometimes Thay taught us songs.

It is thanks to Thay that I know how to sing. I used to say, “I will do anything you teach me to do, but please don’t ask me to sing.” I don’t like singing. So Thay kept asking me to sing. No matter how badly I sang Thay kept asking. Never ever say you dislike something in front of Thay! Then, I started to sing on my own, and Thay caught me at it one day! He proudly told everyone about it. After that, Thay stopped asking me to sing, seeing that he had already succeeded.

When Plum Village got its first Macintosh computer, Thay gave me the handwritten manuscript of his commentary on the Diamond Sutra to type out. I still remember that I used the font “Binh Minh.” Before that, Thay had typed everything with a typewriter. When we got the computer, Thay was so happy and asked me to learn how to use it so that I could type up his books.

When I first ordained, I was very shy. I rarely opened my mouth, to the point that Br. Phap Dang said, “It seems that Sr. Doan Nghiem doesn’t say more than ten words in a sentence.” When I did speak, I said only a few words so it sounded a bit curt. When Thay gave me his handwritten manuscripts, he said, “Learn to pay attention to the way Thay writes and edits. You have to read all the parts Thay has crossed out and ask the question, “Why?” So I just asked for the sake of asking without knowing why Thay crossed out this word and replaced it with another. Asking, without ever receiving an answer. Over time, I could slowly understand and was able to make differentiations. Only with direct experience can we understand. With each correction, the writing was improved. That is what I learned and treasured most while working on books with Thay.

Thay never reprimanded me, even though I know that many people complained to Thay about me. I don’t know why I cried so easily in the first few years of my monastic life. Whenever someone “informed” Thay about me, Thay called me to the Hermitage. Upon arrival, as I opened the door, there was Thay in his long robe, sitting solemnly in the middle of the room waiting for me to come in. As soon as I bowed to Thay and sat down, I started to cry, so how could Thay reprimand me? I don’t know why I cried. I thought about my hot temper, my inability to express my feelings, my rough words… If I had heard more, I would have been lost even further in my thoughts, so Thay said nothing. That’s what I thought anyway.

With more time in the practice, I could feel and appreciate Thay’s love for me, and I want to continue Thay in this regard: to love and not reprimand my younger ones. I think everyone needs an opportunity to change. I have changed, so I trust that my younger ones will change also.