Transforming Resentment into Compassion

Brother Chân Trời Định Thành

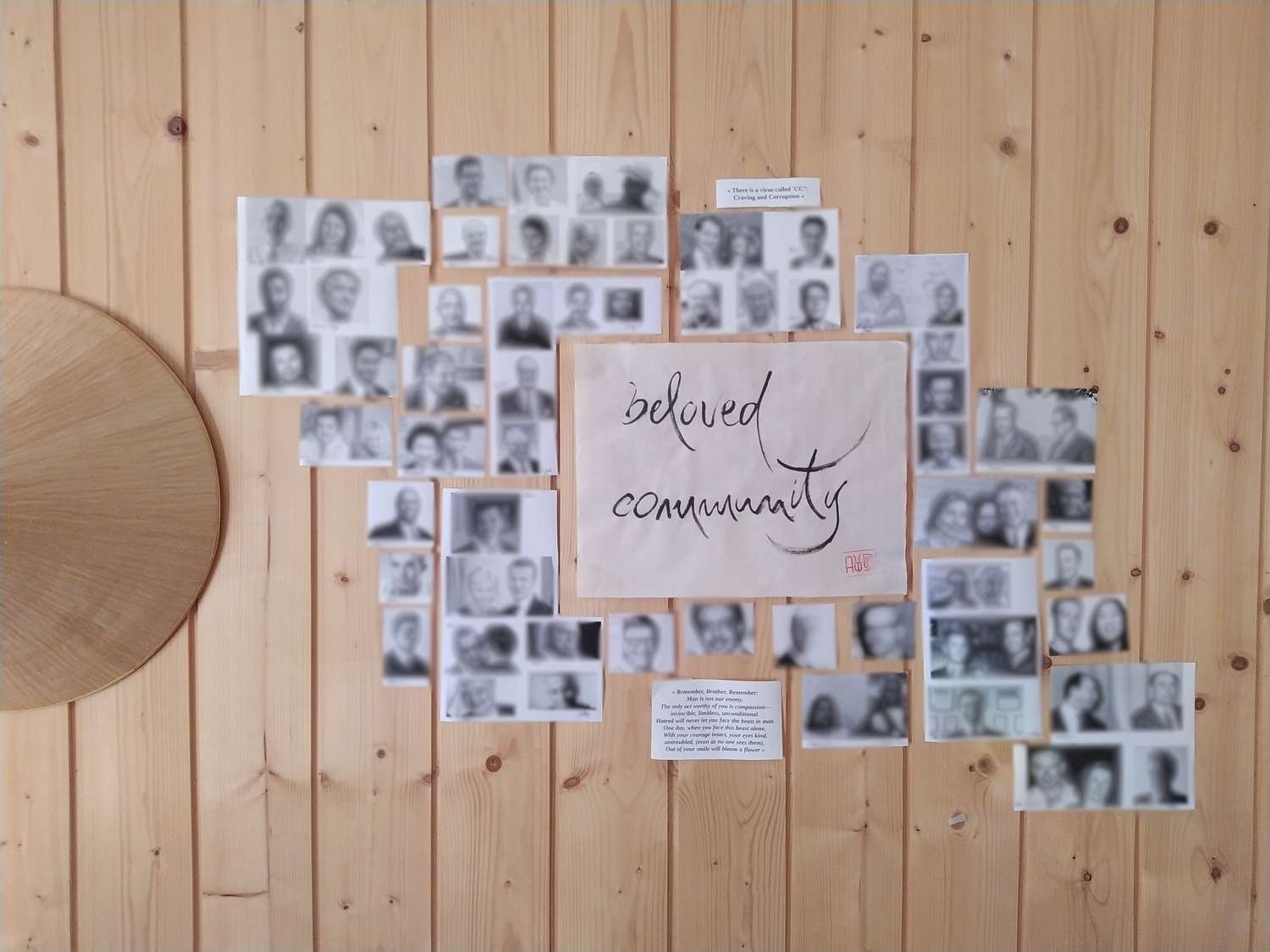

Last year, in January 2022, a few days after I ordained as a monk and moved to the monastic residence, I asked my ordination brother, Br. Dinh Tuc, to craft a calligraphy for me with the words “Beloved Community.” This phrase was used by Martin Luther King, Jr. to refer to the Sangha, the community of practice.

I posted this calligraphy on my bedroom wall in order to remind myself of inter-being rather than that of separate individuality. It worked for a while, but over time it became too familiar and I forgot the intended message. It needed to be renewed.

This calligraphy soon found a new vocation during summer. It all started with an intuition that dawned on me while chanting Namo Avalokiteshvaraya with the community. In the third round of chanting, I made an effort to extend my compassion to some individuals I resented in the political, media, and financial spheres for their deeply harmful actions. Indeed, as an observer and actor in the field of ethics of my society, at times, the sight or evocation of certain figures in the media-political field tended to provoke anger and resentment in me.

Man is not our enemy

I wished to connect with these individuals in a more profound way: to connect with their humanity. I searched the internet for their photos and selected those in which they appeared at their best, that captured their most humane moments, for example, when they were children, in their family, or with their partner and children. I printed them and wrote their first name — rather than their surname — underneath the photo: ‘Bill’, ‘John’, ‘François’…

Then, I placed all the photos around the calligraphy “Beloved Community” as if to say: “I want to include you in my beloved community, regardless of what you’ve done, regardless of what you do.” It felt like a prayer.

I also placed next to the collage a quote from Thay:

“There is a virus called CC, craving and corruption”

Everything in the world is interconnected

As weeks went by and photos were added, my relationship with these people transformed. The charge of resentment and anger toward them dissipated and gave way to empathy and greater space in my heart, notwithstanding the inhuman acts I attributed to them. I no longer saw their acts as isolated, but collective, caused by a collective disease, by the same viruses. I saw that their actions were driven by greed and fear — fear of loss, fear of deviating from the group to which they belonged, and conflicting loyalties. I realized that if I had been born into the same family, if I had been influenced by the same people, educated by the same mentors, I would be just like them, and I would undoubtedly have participated in the same atrocities.

“We, Sons of Eichmann”

My contemplation also helps me see that the photos placed around the calligraphy are only the visible faces of a profound dynamic that involves many others, active or passive accomplices, who are not visible. Without the passive complicity of the population, of which I am a part, could these acts have occurred? Why, then, keep an emotional charge against these individuals alone?

In “We, Sons of Eichmann”Translated from the book “Wir Eichmannsöhne: offener Brief an Klaus Eichmann” by Günther Anders, Page 19 Günther Anders proposes the following reflection:

“What do I call monstrous?

That there has been institutional and industrial destruction of human beings; and by the millions.

That there have been leaders and executors for these acts: servile Eichmanns (men who accepted this work like any others, and exonerated themselves by referring to orders and loyalty) […]

That millions of people were placed and kept in a situation where they knew nothing about it. And didn’t know because they didn’t want to know; and didn’t want to know because they had no right to know. So millions of passive Eichmanns.”

The atrocious and long war in Vietnam would not have been possible without a sufficiently favorable American public opinion — sufficiently favorable because the public was kept under disinformation. Hence, Thay’s courageous departure for the United States to reinform the American public and call for a halt to the war — a departure which earned him exile from his country.

Thay’s example is nourishing in many ways. Before acting, he took the time to analyze the situation in depth, in order to obtain the most accurate vision possible. In his book, Lotus on a Sea of Fire, published in 1967, Thay wrote no less than 70 pages analyzing the historical framework of the Vietnam war and looking deeply into the difficulties of the time he was writing, before making concrete proposals and taking action.

Following this contemplation, I continue to do my best — according to my ability and availability — to inform myself in depth and speak openly about the attacks on human dignity in my society, as the 14 Mindfulness Trainings invite me to. I note that following my creative experience with the calligraphy, I no longer fall so easily into the bias of resentment against political and media figures. I see them in myself, I see the causes in myself and around me, in my society. It’s a real transformation, which is necessary to reestablish the human connection and enable me to take just and beneficial action, however modest. Here, in the beloved community of Plum Village, the multifold Sangha, it seems to me that we have the best conditions to do just that.

“The only thing worthy of you is compassion

–invincible, limitless, unconditional.

Hatred will never let you face the beast in man.

One day, when you face this beast alone

with your courage intact, your eyes kind, untroubled (even as no one sees them),

out of your smile

will bloom a flower.

And those who love you

will behold you

across ten thousand worlds of birth and dying.”

from the poem “Recommendation”