The Presence of Thay

Sister Chân Trăng Bồ Đề

Sister Trang Bo Đe is of Vietnamese origin. She ordained in 2016 in the Kanikonna Tree ordination family at Thai Plum Village. She has been residing, practicing and serving at New Hamlet, Plum Village, France, since 2016. She is great at playing with children, as well as having fun in teaching Vietnamese to her non-Vietnamese monastic siblings.

Under the illuminating blue sky

I suddenly feel

The presence of Thay…

The walking meditation paused at the top of the hill; everyone was gazing at the serene blue sky and enjoying the warm sunshine. There was no sense of a separate self in that moment. In the garden of the sangha, each person has their own way to continue Thay; so much so that sometimes it seems difficult to have a consensus. Nevertheless, I think as long as we still treasure Thay’s teachings on mindful walking and breathing, treasure the value of participation in the sangha’s scheduled activities such as walking meditation, then the sangha will still flow in the same direction.

The sound of the town church bell in the distance echoed at intervals across the spacious sky. The sangha breathed in synchrony at that moment.

During this Rains Retreat, the time for walking meditation on our monastic Days of Mindfulness truly became an opportunity for me to practice the art of stopping, to let go of my thinking and mental to-do lists, and return to the present moment, to simply be aware that I was walking. After two morning classes, there was nothing more wonderful than being outdoors, breathing in the fresh air and playing with nature. Walking meditation was the time to play for me.

“The bell is calling.

Our feet kiss the Earth.

Our eyes embrace the Sky.

We walk in mindfulness.

Ten thousand lives can be seen in a single instant.

This is still springtime,

when everything is manifesting itself

so rapidly.

The snow is green.

And the sunshine is falling like the rain.”

from the poem “Cuckoo Telephone”

I remember during grade school, my friends and I would long for the school bell to ring so that we could immediately close our books and pour into the canteen to buy snacks and sweets. The two morning classes on the monastic Day of Mindfulness brought me back to the elementary school days when I learned to befriend the written words, blackboards and white chalk. For the sake of the younger monastics, the elders converted the classic schedule of morning Dharma talk and afternoon Dharma sharing sessions into classes on various topics throughout this Rains Retreat. There was a class on how the mind and brain affect our lives by Sr. Hoi Nghiem, a class on Buddhist psychology by Sr. Tue Nghiem, a class on comparative ethics by Sr. Hien Nghiem, and a handful of other classes. These classes had succeeded in sparking enthusiasm among monastics, kindling a unique vivacity for this memorable Rains Retreat.

10 parts studying to 1 part understanding

The enthusiasm of the Dharma teachers leading the classes seemed to be endless. Right after leading a class on an in-depth understanding of the precepts, Sr. Chan Duc immediately went to the next class to teach Pali to a smaller group. Sister Chan Duc taught us the Pali version of some of the familiar sutras, such as the Discourse on Turning the Wheel of the Dharma, Discourse on Knowing the Better Way to Live Alone, and Discourse on the Full Awareness of Breathing with immense patience and inclusivity.

Reality proved that the enthusiasm of the transmitter was unlimited; however, the ability of the receiver was… limited. I often could not help feeling embarrassed over my ability to understand only one part of the ten things taught. Usually, we took turns to read one sentence in Pali and then translate it into English based on our understanding. Whenever it was my turn, I did my best to express good intentions to befriend the Pali alphabet. Despite my sincerity, those alphabet friends were determined to ignore me as though we were strangers, causing me to mumble and stutter incoherently, desperate to find an escape from my tangled mess. Many times, my reflexive, come-what-may, do-or-die answers would make the class burst into laughter.

In fact, we brothers and sisters “functioned as one body” in the class. Whenever, one person was “in crisis” with a Pali question, the whole class would rapidly toss their “life jackets” to rescue our sibling; but alas, there would be so many life jackets at once that the sister or brother would not know which one to take. Luckily, Sr. Chan Duc compassionately let us pass regardless whether our answer was right or wrong. And I breathed a sigh of relief.

Despite my ability to learn only a fraction of what was taught, after three months of using diligence to make up for not being a smart learner, along with the guidance from Sr. Chan Duc and encouragement from fellow monastic classmates, I was able to gather a few Pali words for my pocket and memorize a segment of the “Four Recollections” chant:

Itipi so bhagavā arahaṁ sammā-sambuddho,

Vijjā-caraṇa-sampanno sugato lokavidū,…

Every hour in class is a source of joy

After five sessions of in-depth learning about the Great Bhikshu/Bhikshuni Precepts, the brothers and sisters had three classes to choose from for the first of the morning classes. We could either choose to continue with the class by Sr. Chan Duc to further discuss the precepts and offer our insights on how to revise the Great Precepts; attend the class by Br. Phap Huu on Plum Village monastic culture; or join the workshop by Br. Troi Bao Tang and Sr. Trang Tam Muoi on how to apply Thay’s teachings to contemporary issues in the West. Skimming through the three topics, I felt curious and inspired to learn more about monastic culture. So I signed up for that class. Although it was different from how I imagined it would be, I still felt that each hour in class was a source of joy.

We got to hear about the “origin stories” of the 5-year monastic program, of hugging meditation, of the annual tradition of the monastic brothers and sisters taking turn to touch the Earth in front of each other in the Lunar New Year ceremonyA Plum Village practice for the monastic sangha since 1999. During the annual Lunar New Year celebration, the monks would stand facing the nuns, while the nuns sit still with joined palms. One monk would read aloud a text recognizing the presence of Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Great Compassion, in every nun, and declaring the vow to practice their precepts properly to protect their monastic path and the monastic path of the nuns. After the reading, the monks would prostrate three times in front of the nuns. Then the nuns would do the same, but reading aloud a text recognizing the presence of Samantabhadra, the Bodhisattva of Great Action, in every monk; subsequently, the nuns would prostrate three times in front of the monks., of how Thay simplified the religious Buddhist practices so that the teachings of the Buddha could be applied in Western society on the basis of mindfulness practices, etc.

Through his easygoing demeanor, witty storytelling ability and open-mindedness, it was captivating to listen to Br. Phap Huu share about Thay and the traditions of Plum Village. “Did you know, brothers and sisters, that when I and a group of young monastics performed a rap song for the first time in the history of Plum Village, a few monastics in the audience questioned whether or not it was appropriate for the monastic fine manners and if it was suitable for the environment of a monastery? This reached Thay’s ears and he invited me to see him at the Toadskin Hut. Sitting across from Thay, I thought Thay would surely reprimand me. But, no. Thay only smiled and said only one thing: ‘This is my kind of Buddhism.’”

Beyond the words shared, I could see the everlasting fire of enthusiasm Thay had successfully ignited and nourished in the young disciple Phap Huu of the early days so that now that fire could be transmitted to this younger generation. I could also see Thay’s image, mannerism and insight reflected in the heart of the Br. Phap Huu of present-day. I sensed that the things Br. Phap Huu endeavored to transmit to us was the spirit, insight, and the person Thay was.

The Net of Indra

Learning to look with the eyes of non-self, the presence of Thay permeates the sangha: on the walking path lined with pine trees, on the Buddha hill, and at the Sitting Still Hut; however, the place where I can see the presence of Thay most vividly is perhaps in the hearts of my elder brothers and sisters. If someone said that “Thay is conservative, always wanting to preserve the essence and beauty of Buddhism,” I would agree. At the same time, if someone said that “Thay likes to experiment, always willing to try something new,” I would also not hesitate to agree.

Each disciple interacted with Thay at different times and stages of Thay’s life, not to mention Thay’s forms, feelings, perceptions, mental formations, and consciousness also continually changed like everything else in the flow of life. I think no one could confidently assert that they had 100% understood Thay, because Thay was an ever-changing manifestation that could not be grasped. Perhaps, the thing that we preserve is the image of Thay in our mind. It is neither real nor unreal.

I remember Sr. Chan Duc shared that after returning to Plum Village from a trip in India, Thay gave her a Pali dictionary. That was when she began learning Pali. I think, aside from Thay’s immeasurable love, the thing that is profoundly instilled in the heart of each disciple is Thay’s deep understanding of his students. Thay understood the personalities of his students; and, accordingly, placed them in positions suitable for them to be themselves while developing their strengths and contributing to the career of sangha-building.

For me, the sangha is the Net of Indra with each person as a multifaceted jewel reflecting the image of Thay, as well as their own. Whenever I hear stories about Thay, I do not need to think whether or not it is correct; but, rather, depending on my state of mind at that time, I will decide the direction in which I want to go. Throughout my journey on this path, I think I have, once in a while, touched the essence of Thay.

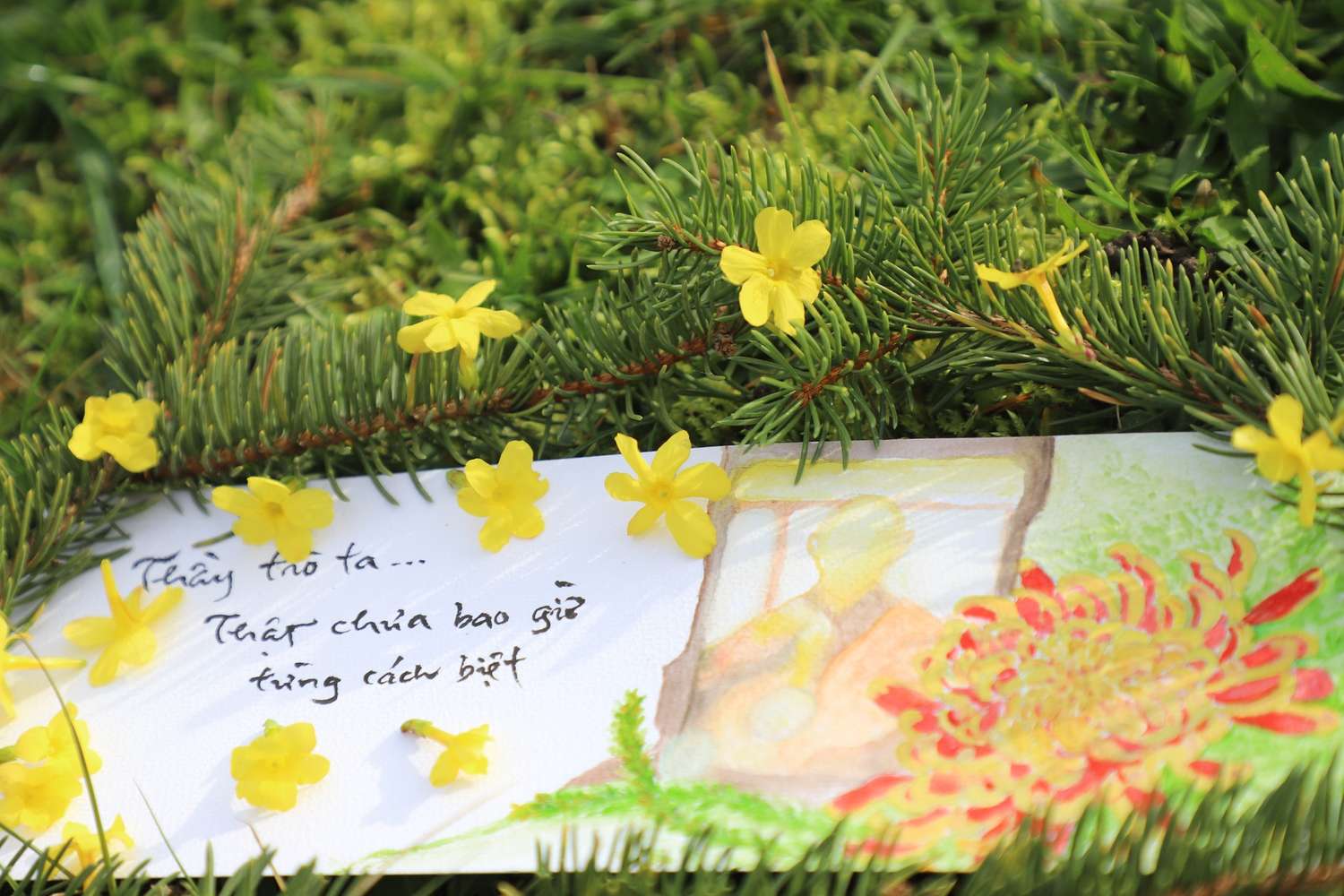

Thay’s presence in me

I have never experienced war. I was not there with Thay in the early days of Plum Village. I was not even there with Thay on the teaching tours. Nevertheless, there are times when I feel profoundly connected to Thay.

“The one who bows and the one who is bowed to

are both, by nature, empty.

Therefore the communication between them

is inexpressibly perfect.”

The presence of Thay in me is like the bright moon amidst the dark night sky. Even if the clouds completely obscured the moon and stars, I would still see Thay light up the torch of faith and hope in me.

“Who knows that in the pitch-dark night there is a child quietly crying.”

In the thick of a storm, Thay transformed into poetic verses to calm and comfort me, offering me warmth and understanding, and gently helping me soothe the hot tears.

“I hold my face in my two hands.

No, I am not crying.

I hold my face in my two hands

to keep the loneliness warm–

two hands protecting,

two hands nourishing,

two hands preventing

my soul from leaving me

in anger.”

from the poem “For Warmth”

The great poet, Nguyen Du, once wrote, “The body may have transcended, but its essence remains” (Thác là thể phách, còn là tinh anh). Thay is an incense that has burned to its end, but its fragrance will permeate the air for eternity.