Lessons From My Teacher

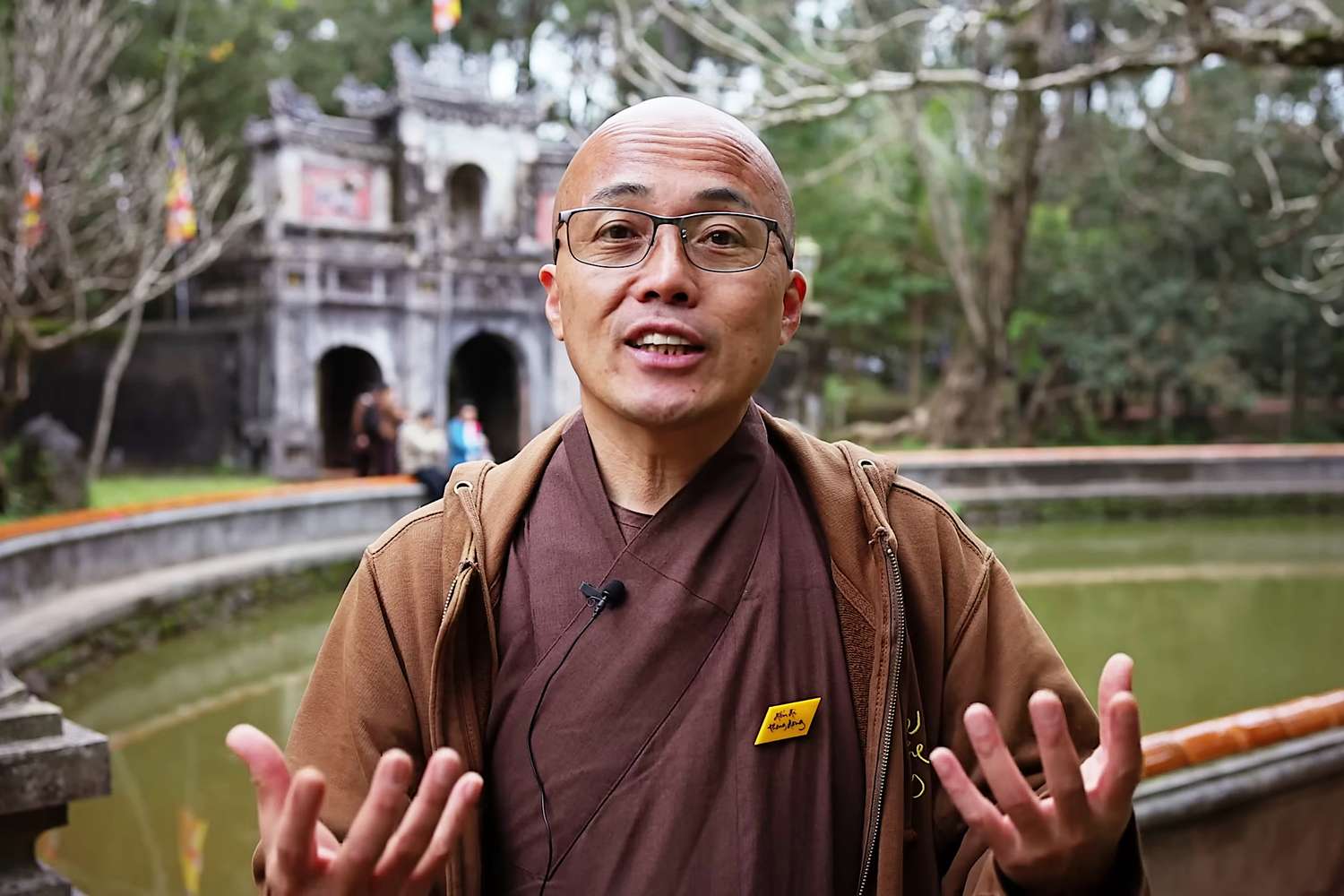

Brother Chân Pháp Dung

On 27 January, in Hue, Br. Phap Dung shared about his first encounter with Thay and his experience returning to Hue for Thay’s 2-year grand memorial.

As a young man growing up in the US, I rejected everything that was Vietnamese. I did not know at the time that it was a kind of internalized racism. I wanted to belong and to be like the people around me. I remember feeling ashamed of the lunch I brought to school because it smelled “weird.” Even though I loved it so much, I would find a corner far away from everyone to eat it.

I didn’t know many other Vietnamese people. Then, when I was studying architecture in university, I won a scholarship to go to Vietnam to study “Vietnamese architecture”! I thought to myself, “I better get to know some Vietnamese people.”

That was in 1995 and Thay was in California leading a retreat. That’s how I first met Thay. It was a retreat for Vietnamese people in the US, and Thay focused on healing intergenerational conflict and trauma as Thay would often do at retreats for Vietnamese people abroad. So many of us had grown up in the West and felt alienated from our parents’ generation. Thay did his best to help us understand and reconcile with each other.

For me, it was the first time I had some understanding of my father’s experience of the war and understanding his anger.

I remember going home after the retreat and one day, for some reason, I was very angry with my father. But instead of slamming the door to show my anger — that was how many of us communicated nonverbally in the house — I made the commitment to sit and breathe. I thought, “I will just sit and watch this anger and not say or do anything until it passes.” I did just that. And I sat until the anger subsided. It was a real revelation and triumph for me, to be able to master my anger like that. I know it may seem something small to you, but for me, it was mind-blowing to have sovereignty over my anger. That was the start of my journey of healing my relationship with my father.

I remember seeing the young monastics at the retreat with Thay, who were so different from the Vietnamese monks that we would often encounter in the US. The elderly monks looked as stiff as rocks. But these young monks and nuns were so joyful and lively.

At one of Thay’s talks, it was very solemn on the stage, but behind Thay I could see these two young nuns poking each other. I am pretty sure it was Sr. Dinh Nghiem and Sr. Tue Nghiem! I was so surprised to see them laughing and having a good time.

It made me curious about Thay’s community. I was still very suspicious. I didn’t believe that the monks and nuns could be smiley and joyful all the time, so I decided to follow them on their US tour! What I didn’t know was that Thay had noticed me and had asked Br. Phap Niem to observe me!

I stayed with them in various lay friends’ homes, sometimes 30 of us in one house and sharing one bathroom. I still remember all the monks standing in a circle around a patch of lawn and brushing their teeth together. So simple and so joyful all the time!

Coming to Vietnam this time, I am using Thay’s life as an object of my contemplation. To see the environment that Thay lived in, to understand the circumstances he met, and to learn from the decisions he made. Thay never wanted us to be dogmatic and to have a fixed set of rules to live by. He just wanted us to be mindful and to learn how to respond to each changing situation ourselves.

When we learn the life of Thay and of our ancestral teachers, we are bringing history into the present moment. It is not something archaic that only belongs to the past. It is very much influencing our present, and forming our future. It is important to ask ourselves how their lives continue to be relevant in our time.

Thay has helped us learn to dwell in a country of the present moment. One that is without frontiers. Today, as we are surrounded by monastics and lay practitioners from over 30 countries, we really see how the practice of dwelling in the present moment helps us transcend time and space.

When we walk together in the Root Temple, we only need to dwell in our steps and be aware of our breath. We don’t need to do anything more. That is already continuing Thay. When the people in Vietnam see an international delegation walking mindfully around the half-moon pond, they know immediately that we are Thay’s disciples. That is all we need to do.