Sun-Bleached Brown Robes

Brother Chân Pháp Ứng

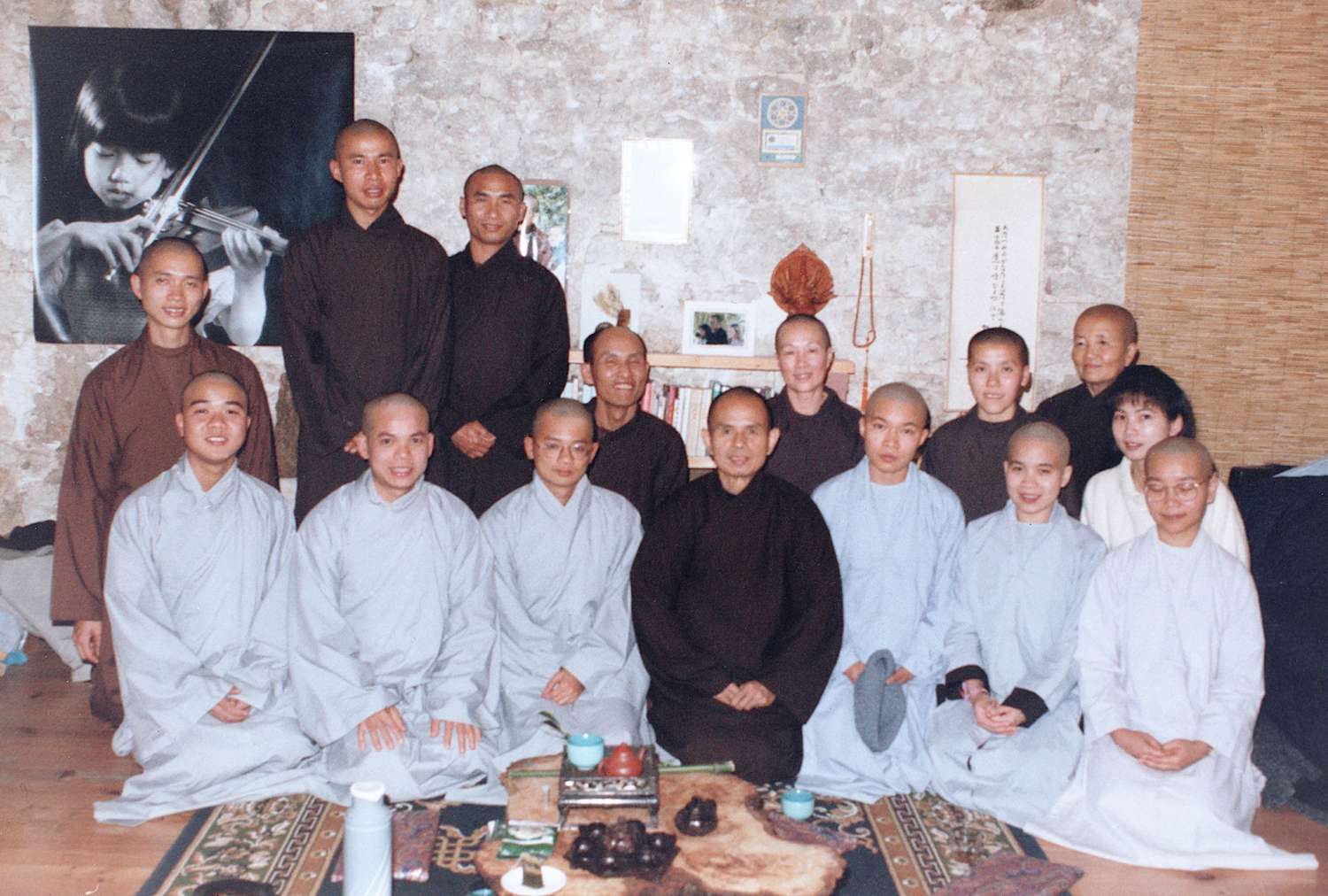

On 11 December 2023, the monastics of the Fish ordination family turned 30 years old. After 30 years, the number of “fish” has reduced to two-thirds, from six individuals down to four. Now, they are elder brothers and sisters of Plum Village. Brother Phap Ung is one of the remaining four “fish,” alongside Sr. Thoai Nghiem, Sr. Dinh Nghiem and Sr. Tue Nghiem. On this occasion, the editorial team had a chance to drink tea with Br. Phap Ung at Thay’s hut in Upper Hamlet.

An ancient seed deep in the Earth just smiles

After 30 years of being guided by Thay and nourished by the sangha, I feel like I have nearly completed a period. Just as there are four seasons in a year with leaves falling in the autumn and new buds manifesting in the spring, I have experienced all sorts of changes.

During those years, I have made all kinds of mistakes, learned to get up from a fall, and incurred many scrapes and scratches, so to speak. Perhaps, it is because of these experiences that I feel like the fruits and flowers are beginning to take form; the buds are now just beginning to open. I am beginning to recognize and have faith in the teacher within myself. This is incredibly precious to me. In truth, however, it is not anything new. It is the feeling of being able to return to myself, like returning to the source in order to continue forward. Maybe it is the essence transmitted by the ancestors that is now beginning to blossom in me. It is like a continuation.

When I had the aspiration to become a monastic, my family was not ready to receive the news. I felt sorry for myself and cried alone in my bed. While crying, I suddenly saw a figure with a glowing complexion who kindly said, “Rest assured, my child!” It calmed me down… Not long after that, I met Thay at a retreat in the Netherlands. Thay looked at me – maybe because I looked naive like a young student or a scout of a Buddhist youth group – and asked, “Do you want to be an engineer of Buddhism?” I thought to myself, “Huh? What’s an engineer of Buddhism? I don’t understand.” I looked confusedly at Thay, but the seed had been transmitted. A seed that has lain deeply in the Earth for many years just smiles.Adopted from the poem “Cuckoo Telephone” in Call Me By My True Names by Thich Nhat Hanh, 2022.

Photo Courtesy: Simon Chaput

Taking care of birth and death is the greatest happiness

Thanks to Thay, my greatest happiness of becoming a monastic was fulfilled. My aspiration was to find a path that could transcend birth and death. In the past, my idea of becoming a monastic was to go to another world, as if to say “bye bye” birth and death. However, Thay taught that we do not need to say “bye bye” to birth and death; rather, we only need to take care of our notions of birth and death. We do not need to run away from suffering; do not need to go to another world. If in our daily lives we have happiness, joy, a bit of something to offer to the world, and the ability to generate love and understanding within ourselves, only then will we be able to take care of our suffering and the suffering of the world. Our lives will have a clearer meaning.

I have been able to come home to the island within and be in touch with myself. Through the lens of the historical dimension, I understand that there is birth and death, there is suffering. At the same time, I can also learn to touch the ultimate dimension: the no-birth, no-death nature of life.

I feel very fortunate. This may be the merits of my blood and spiritual ancestors from countless past generations.

“Stick of the Zen master”

During the years serving and learning from Thay, I received many “Zen sticks.” Thay’s Zen sticks would strike swiftly to the heart’s core because they were usually unexpected. I had the tendency to avoid clashing with anyone. I would choose instead to compromise to make things easier. If I needed to go on the frontline, I would; but I preferred to be in the background more. This was with regard to building sanghas in Vietnam. At the time, I was in Vietnam and Thay was in France. The Zen stick struck when Thay admonished me over the phone (Thay rarely communicated by telephone). I felt so sorry for myself then but later on, I was very grateful to Thay for it. Thay wanted me to grow up, to take action and do the things that needed to be done. Thay gave me the Zen stick to help me be stronger, to have agency and give my input with more inner freedom, rather than always trying to keep harmony by following others.

Patience is the mark of true love

It was not until 1996 that Upper Hamlet and New Hamlet had an abbot and abbess, respectively. Before that, each Hamlet only had a head of the sangha, service coordinator, etc. Perhaps Thay wanted to train me when I was just a novice and then a young bhikshu, because he nominated me into the council of elders, consisting of “venerables,” like Br. Giac Thanh, Br. Doji, Br. Sariputra and Br. Nguyen Hai. I don’t know how I was eventually “put” into the position as head of practice.

One time, at the end of formal lunch, Thay said, “Let’s have Dharma sharing this afternoon!” Being head of the sangha, I “cleverly” said, “Dear Thay, let us look it over. Let us discuss it.” The whole sangha was startled, wondering “who was this audacious young monastic?” A lay friend sitting next to me, named Tinh Thuy, who later became Sr. Quy Nghiem, whispered, “How could you?!”

Later, I slowly got it. But at that time when I answered Thay, I didn’t understand what I had done wrong. I was taught that the bhikshu council was a democracy; so I applied it right away. When Thay heard my response, he didn’t say anything; he only breathed.

Thinking about it now, I feel deep sympathy for Thay. Thay kept quiet about it for who knows how many years. He was very patient. Perhaps, Thay thought, this young one was slow and needed time to ripen somewhat before Thay could say anything.

Once, we were in the Sitting Still Hut of Upper Hamlet. Thay whispered into my ear, I think it was my left ear, “My child, Plum Village is a combination of two key factors: seniority and democracy.” That went straight to my heart. Yet, I wondered why Thay said that, because I had already completely forgotten about the formal lunch incident. Then I remembered; there was a reason.

The life jacket

I have gone through many ups and downs in the past 30 years. During the low moments, my life jacket was my faith in the practice, the loving connection with Thay and the sangha. It was thanks to the support of my ancestors that I was able to ordain, not because of my talent. Thay often said it is thanks to the merit of our blood and spiritual ancestors, including the sangha.

Upon reflection, I saw that the ups and downs I went through came from the ancestral wounds of my blood family, not from external conditions. Those wounds manifested through certain ways of thinking, confusions and doubts. I learned to accept and persevere in exploring how my mind worked. I knew that this path was worthwhile and in-line with my aspirations. Thanks to that faith, I had the strength to keep going. I continued to get up after falling down and took good care of my ancestral wounds. These wounds were so deep that they kept coming back in phases; they wouldn’t subside.

I was lucky to learn that I didn’t have to wait until the wounds completely healed to be happy. I could be happy in the process of taking care of my wounds. I didn’t need to look for external conditions to find the way out, solace or healing. With my faith as a foundation, I practiced to take care, understand and accept the wounds. This faith helped me feel that I was not alone. My relationship with Thay, the sangha, and my blood and spiritual roots helped me stand firm through the storms. I applied what I learned to continue moving forward. On the one hand, I practiced nourishing joy; on the other hand, I practiced healing.

When I became a monk, I also wanted to help ease the suffering of the world. However, even in the effort of helping our blood families, we need the help of the community. We cannot achieve much as a “lone warrior.” One Buddha is not enough.

Presenting the insight gatha

In the autumn of 1994, Thay taught the Discourse on Youth and Happiness. At the end of the Autumn Retreat, Thay suggested that everyone write a song or poem to present their insight. Thay was even going to grade our insight poems. Out of nowhere, I was “gifted” a song! After singing it before Thay and the sangha, I went with Br. Phap Dang to a retreat in Germany. When I came back, I heard that Thay gave my song 7 out of 10 points.

Sun-bleached brown robes,

coming home to the Buddha,

footsteps imprint on leaves.

Fragrance of the homeland

wafts faintly.

You are here

to nourish me

and I live to support you.

Each small step

together move the Earth and sky.

Whether with or against the flow,

all nourish the entire Village.

“Thay is behind you”

While walking in the forest with Thay one day, he said “This is heaven, my child!” Arriving at a narrow path, Thay said “You go ahead.” But I didn’t dare. Thay said again, “Go on.” I had to obey. I could feel that Thay was sending me the message that he would always have my back. Thay also wrote a calligraphy “Thay is behind you” (Thầy ở sau lưng con).

Many of my monastic siblings did not have the chance to meet Thay; but if they are lucky, they would somehow be able to feel that Thay is always present to support them. Although Thay has passed away, his aspiration is still: “May we never have the need to leave the Sangha body. May we never attempt to escape the suffering of the world, may we always being present wherever beings need our help” (from the chant “Protecting and Transforming”).

Thay’s practice is dwelling happily in the present moment. The present moment is eternal, transcending time and space. Being in touch with the present moment can greatly benefit us. I have arrived, I am home. It’s like we have returned to our roots. That is the inheritance, the insight that Thay wants us to have.

After I was ordained, I experienced a great suffering that I was unable to put into words. Only I knew; only I bore its burden. The brothers could feel my sorrow but did not know what had happened. Luckily, Thay was there to listen to me; he understood and loved me all the same. That helped me to heal. That love continued to be my nourishment on the path. I am tremendously grateful to Thay.

The spirit of non-fear

The essence of Thay that I want to continue most is the spirit of non-fear. That quality is very much needed in this time of our lives, of humanity and of the Earth. A spirit of peace, non-fear and courage will help us to have more faith. This is the faith that we can feel in our bones; it can ignite the fire in our hearts and invigorate us, helping us to take care of our suffering rather than hoping for a better future. This quality of non-fear, embodying the essence of compassion, can help us to face violence, destruction and chaos.

Thay is no longer in the familiar form to guide us directly; therefore, a foundation for each one of us must be to come back to take care of and nourish ourselves. From this shared foundation, we can draw our strength. By breathing the same breath and walking the same rhythm, we have the Buddha, the Patriarchs, and Thay with us.

Another important element is to do what we can so that everyone feels comfortable to be themselves living in the community. That is a very practical necessity. To be able to be oneself means that each person has time to develop, to understand the nature of things, to grow up, as well as to be supported and accepted. However, we also need to open our hearts to each other as the glue connecting this sangha of diverse cultures and traditions.

In the gatha that Thay’s teacher (grandfather monk Thanh Quy) gave to him for his Dharma lamp transmission, there is the sentence: “Walking without dispersion and without strife” (Hành đương vô niệm diệc vô tranh). “Without dispersion” is very important. Everyone has an idea of right and wrong. However, from a meta-ethical standpoint, we need to be “without dispersion”; that is, to accept the left and the right, the mud and the lotus. We need to develop and water the qualities that are beautiful, but, at the same time, we also need to accept the things that are not yet beautiful. We take care and embrace the things that are not yet beautiful. We need that essence in a sangha. We also need to practice “without strife” to take care of the three complexes (superiority, inferiority and equality) present in each of us. That is the hallmark of what we need to develop in order [for the sangha] to realize collective awakening: Thay’s dream.