A Thousand Rivers of Moonlight

Sister Chân Hoa Nghiêm

This autumn, two guests from Vietnam, Mr. Thanh and Mr. Huy, came to visit Blue Cliff Monastery. Mr. Thanh, the director of a documentary about the life of our teacher, Zen Master Thich Nhat Hanh (or Thay), contacted us through Ms. Chau Tho, who is the main director of the film. He wanted to ask for assistance from the brothers and sisters to learn more about the places where Thay had visited and lived in the 1960s. This was a crucial period in Thay’s life when he came to the United States to pursue a Master of Arts degree in 1962 and also began advocating for peace in Vietnam.

Brother Phap Khong contacted Princeton University and Columbia University to organize a visit by the film crew and some monastics to the historical sites where Thay had lived. The first location we visited was Princeton University, where Thay had studied. Dr. Brian Shetler gave us a guided tour of the Princeton library, which houses many of Thay’s Master’s theses, and pointed out Brown Hall, where Thay resided.

We did walking meditation on the path from the library to the campus where Thay had walked in the past. On that day, it was strewn with gold and red leaves. As we walked, I felt as if Thay were revisiting his former school with us. Pausing under a maple tree, we sat in a circle and listened to a passage from Fragrant Palm Leaves. Afterward, we sang “Falling Autumn Leaves," a French folk song rewritten by Thay with Vietnamese lyrics. The wind blew, scattering golden leaves from the swaying branches, creating such a beautiful and memorable scene.

Our next destination was the Pomona wood cabin at Ockanickon Summer Camp in Medford, New Jersey. Pomona belongs to the YMCA and serves as a camp for children and adolescents. This was the wood cabin next to the large lake where Thay had sat on a small boat, paddling north on the lake and playing among the water lilies until evening. As it was now autumn, yellow leaves were falling from the trees onto the surface of the lake. I imagined Thay as a young monk sitting contemplatively, reminiscing about his native country, Vietnam, the pain of war there, and Fragrant Palm Leaves (a monastery Thay founded in 1957). I recalled reading Thay’s memoir, Fragrant Palm Leaves, and how my eyes had teared up at the two verses written as a farewell to Thay by Ly, a social activist. Even now, reading them again, my emotions well up:

“On the day you return, if the sky is torn asunder,

look for me in the depths of your heart.”

We sat inside the wood cabin by the wood-burning stove. Mr. Tho (a lay practitioner and close friend of Blue Cliff Monastery) collected leaves and dry wood for the fire. The dry leaves ignited, filling the room with warmth. It was in this very cabin that Thay had written a short book in Vietnamese, titled A Rose for Your Pocket. Later, a musician took a part of the prose and put it to music. Inspired by the surroundings, Sr. Noi Nghiem requested to sing this song in memory of Thay. Everyone joined in, as most everyone knows this song by heart. Suddenly, I remembered the poem “The Joyful Meditation Hut” that Thay had written for Venerable Thanh Tu when Thay was still at Fragrant Palm Leaves Monastery. This poem was later set to music by Sr. Quy Nghiem. In this quiet moment, it felt as if Thay were sitting with us in this room. Suddenly, I wanted to sing to offer homage to Thay and to those present.

“Clouds softly pillow the mountain peak.

The breeze is fragrant with tea blossoms.

…

My confidence intact,

I bid farewell with a peaceful heart.”

from the poem “Untitled” in Call Me By My True Names

Singing up to this point, I suddenly felt my throat constrict, and was unable to continue. Thay has indeed gone far away; perhaps, the faith he entrusted to us was: “Continue the path that Thay has traveled, don’t give up, my child…” I whispered in my heart, “Yes, I will never give up, Thay!”

The next day, we continued our visit to Union Theological Seminary, which is affiliated with Columbia University in New York, to explore the places where Thay had lived during his time there. We began walking meditation from the house at 306 West on 109th Street, where Thay resided before returning to Vietnam in 1963, to Columbia University. The city of New York was bustling with people. Passing the fruit stalls, I imagined Thay buying vegetables or bread alone on these streets in 1962, when his close friend Steve wasn’t around. Those must have been lonely times for Thay. Thinking about this, I felt compassion for him.

During that time, there were almost no Buddhist monks where Thay lived. I thought about this period during which Thay had to confront internal conflicts and feelings of loneliness in this new environment. That young monk also carried the sorrows and intensity of the war happening in his homeland. Thinking about this, my eyes welled up with tears for the young monk, my teacher, who carried such a heavy burden on his shoulders. I didn’t want people to see me cry, so I quickly wiped away my tears. But, I remembered Thay telling me, “If you want to cry, just cry, don’t suppress it. There’s nothing shameful about crying. Being aware that you are crying is enough.” Being aware that we are crying, the tears will naturally stop flowing. When the sun of awareness shines, light will flood in, and we don’t need to suppress our emotions. Being aware that I am crying, how can I continue crying?

Photo Courtesy: Columbia University

In the past, Thay came here alone. When leaving New York to return to Vietnam, did he ever think that there would be a time when he would come back, not alone, but with a whole sangha? At that time, Thay probably didn’t expect that he would later establish a monastery in the New York area, on the East Coast of the United States, where he was once an unknown young monk. Today, Thay has thousands of American disciples, monastic and lay. The continuation of Thay’s legacy is truly unimaginable.

We visited the library of Columbia University, exploring Butler Library on the eleventh floor. Thay mentioned this library in Fragrant Palm Leaves. It was here that Thay opened a book and found that two people had borrowed it before, on dates decades apart. Thay happened to be the third person. He wrote, “I am standing here, meeting them in space but not in time.” Thinking about this, I suddenly felt moved; I too was meeting Thay, a young monk opening a book here, in the space of my own consciousness.

Caro Bratnober, the public services librarian at the University, gave us a guided tour during the visit, stating that everything in the library was essentially the same as before, with few changes, except that they had changed the call numbers on the book covers to correspond with numbers in the computer system. Looking at the bookshelves, my heart marveled! Time had passed, but the space remained as before. Many generations of scholars had walked past these bookshelves, including my teacher.

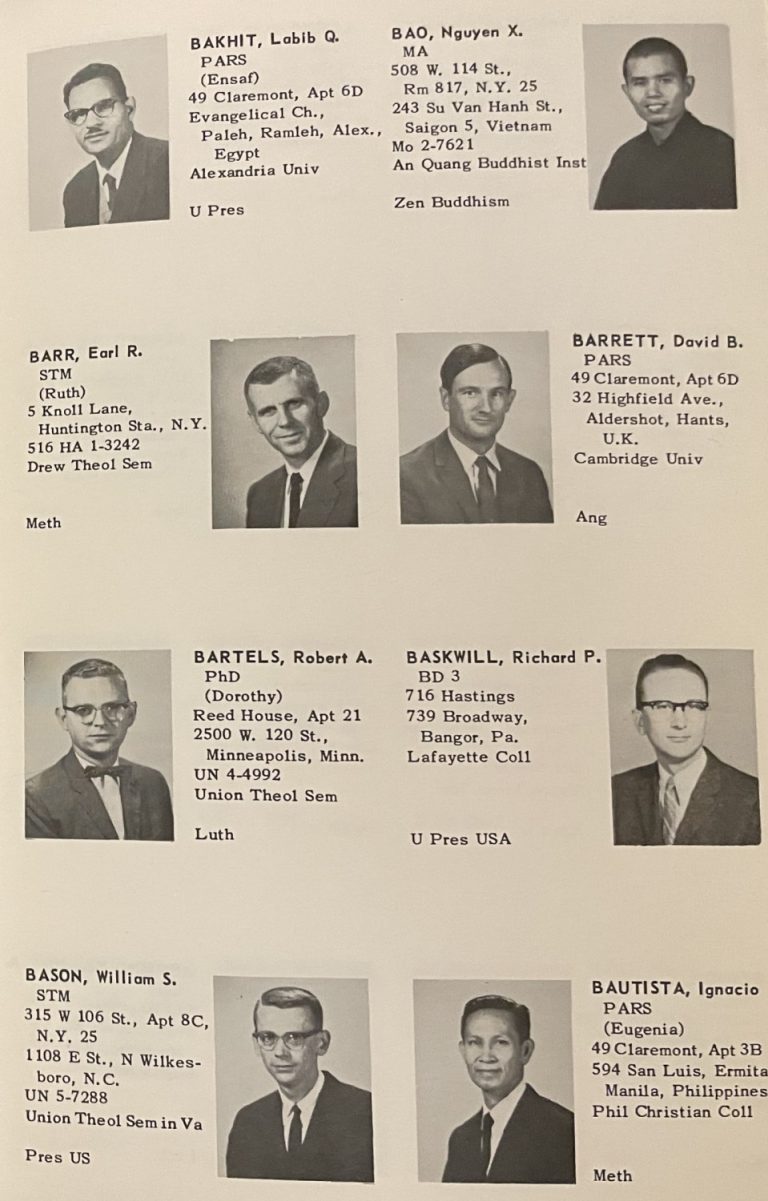

Caro then took Br. Phap Khong and me to Burke Library, another library on the upper floor, where students could study and conduct research. They led us to a small secluded room displaying pictures and materials about the founders of the school and the professors who had taught here. I was surprised to see a picture of Thay in a glass case alongside other renowned professors of the university. Thay looked very young, around 36 years old. They displayed his Master’s thesis with his research topic, titled “The Problem of Knowledge in the Philosophy of Vijñānavāda." I felt a sense of pride and admiration for my teacher: A young monk could eloquently present the epistemology of Buddhist philosophy, a relatively challenging doctrine, in the Western academic environment where Buddhism was still quite unfamiliar at that time.

Mr. Thanh also wanted to visit Riverside Church, where Thay gave a talk on September 27, 2001, after the Twin Towers were attacked on September 11. When we arrived, it was already quite dark. Initially, those inside the church didn’t want to receive us, saying that they had closed. But upon hearing that we were making a documentary about Thay life, an elderly man in the church told the security guards to let us in. The kind elderly man welcomed us and took the delegation to visit the hall, where Thay had given his talk to 1,500 people. He had been present among the audience. Brother Phap Khong mentioned that he was not yet a monastic at that time and had also sat among the audience, listening to Thay talk.

I still remember that year: We were on our way to Kim Son Monastery, California, when we heard the news that the Twin Towers had been attacked. Thay asked the driver to stop the bus and told all of us to join our palms and recite the names of the Buddha and bodhisattvas to pray for those who had died in that terrorist attack. Afterwards, the US sanghas invited Thay to give a Dharma talk at Riverside Church because the American people were in a state of fear and desire for retribution. Some of us who accompanied Thay to the church that evening were very worried, including me. I was afraid that a bomb somewhere would suddenly explode while Thay was giving the talk. But Thay was very calm. Thay said that we needed to practice fasting to pray for peace in America, and no matter what, Thay had to give them a Dharma talk during this period of time. Upon arriving, Thay, with each steady step, walked into the church. Each one of us took mindful footsteps up to the podium. Sitting on the podium behind Thay, I felt ready to accept anything that could happen to me at that moment, even if I had to sacrifice my life. The main content of Thay lecture that day was how to embrace our anger.

The vow of a bodhisattva is not to be afraid, not to think only of oneself, and to dare to speak out and call for peace in the world. Our society today needs many bodhisattvas to speak up together for world peace. One bodhisattva is not enough. We need a sangha, for only a sangha can create a mountain that can withstand the storms of war.

The Bodhisattva Vows are something that I learned from Thay’s teachings. They include the path of the Bodhisattva of Great Understanding, Manjushri, who uses wisdom to cut off all afflictions, and courageously faces violence and hatred without fear. The path of the Bodhisattva of Great Action, Samantabhadra, is to bring the practices of Love and Understanding into life. The path of the Bodhisattva of Great Compassion, Avalokiteshvara, is to help reduce people’s suffering through the practice of immense love without discrimination. The path of the Bodhisattva of Great Aspiration, Ksitigarbha, is not to avoid suffering, not to find a peaceful place just for oneself, but to commit to go to the places that need help. It was only much later that I understood Thay’s fearless actions in giving the Dharma talk at Riverside Church at that time.

In the water of a thousand rivers, the moon appears

The day I asked Thay to ordain as a nun, I simply thought that I wanted to become a nun because life in Plum Village was so fun. There was nothing to worry about. Every day I could do sitting and walking meditation with the sangha, eat in silence, and every week I could listen to Thay’s Dharma talk. I didn’t need to look for a job or compete for an important position, nor did I need to think about money. Life was so simple and happy. But over time, I gradually saw clearly that the path I was on was not as simple as I thought. I began to have work and responsibilities assigned to me by the sangha. I became more worried about monastic life, because at that time, Plum Village was not as developed as it is now. I started thinking about how to raise money for Plum Village so that we would have enough to live by.

I asked Thay for permission to keep bees to sell honey, because Plum Village has up to 1,250 plum trees, and every spring, they bloom and bees fill the garden. I also had other ideas like making spring rolls to sell at the market in the local town of Sainte Foy on Saturdays, etc. Thay shook his head, looked straight into my eyes, and said very firmly: “Don’t worry my child, just keep practicing! If one has virtue through their wholehearted practice, one will not lack for food. Instead of worrying, you should take Transformation and Healing as a book for your bedside table and read one chapter a day for me.”

Starting from that day, every night I read Transformation and Healing, a commentary that Thay had written about the practice of the Four Establishments of Mindfulness. The text is very simple and easy to understand. Reading it, I felt like I had just struck gold. The path of transformation has helped me transform my habits every day, giving me a new perspective on life, showing me that my true homeland is right inside me, not somewhere far away.

One time, Thay told me: “Out there, people are suffering a lot. They really need our help, so we should study and practice properly.” I nodded, joined my palms, and replied, “Yes.” At that time, I could only agree, but my mind was blank. Over time, however, I’ve had the opportunity to go to many centers and come into contact with the many cultures and diverse lives of many people. Regardless of nationality, race, skin color, or class, wherever people are, they cannot avoid suffering in life.

I have been residing at Blue Cliff Monastery for nearly ten years now. Living in a wealthy country like America, I thought that there would be less suffering than in poorer countries around the world. But I was wrong. The suffering here seems as full as the Atlantic Ocean. I know of a family whose son had committed suicide. I listen to students who have wounds from sexual or physical abuse by their parents. There are people who feel lonely in their lives. There are young people who have been mired in addiction, debauchery, etc. Of course, there are also beautiful aspects of life. But what I want to say here is that even an economically developed country has its downsides.

Recently, a sizable crowd of people regularly shows up for our weekly Day of Mindfulness at the monastery. More and more young people come for the first time and then return. I can see that the need for the practice of mindfulness is very strong, because the world has more and more conflicts, wars, global economic recessions, unusual climate changes, natural disasters, and depression. Stress causes many young people to commit suicide. Occasionally I hear of young people committing suicide in New York or in Washington, D.C. The pressure must be tremendous in order to make people take their own lives like that. There is also much mental illness in society. Most recently, I had direct contact with a young woman who told me, “There is an evil spirit inside me that keeps urging me to stab myself or hang myself. I was so scared that I ran here.” I advised her to recite the name of Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara whenever she heard the voice in her head to help her deal with her paranoia. Even though I tried to help her, after she left Blue Cliff Monastery, I heard that she had stabbed herself. Luckily, she was saved. But, in situations like this, as parents and siblings, what must we do to help our loved ones overcome emotional storms and distress? Isn’t it too late to wait for the storm to come before finding a solution?

When I see young monks and nuns interacting happily with young people, being their companions in the practice as well as in service, I feel very happy. I hope Blue Cliff Monastery will be able to receive more and more young monks and nuns here to live and study.

I clearly see the reason for my presence and my practice here. I clearly see that I am not practicing only to achieve my own personal goal of enlightenment. My existence and practice is to help alleviate the suffering of those who are in need of help and love. Every time I come back from a long trip, I feel that Blue Cliff Monastery is a peaceful place, my home.

Tonight, the moon is so bright outside the window of my room, it reminds me of the year I sat with Thay on a bench watching the moon. Thay told me: “Only when we are free, can we see the bright moon…” Did Thay want to tell me that only when I am not busy with family or social matters, only when my heart is not filled with desires, wishes, and sorrows, only then will I be able to truly be in touch with the bright moon? As Thay’s parallel verses in the Great Togetherness Meditation Hall of Blue Cliff Monastery says:

“Nước Bích lắng trong, ngàn sông có nước ngàn sông trăng hiện.

Non Nham tú lệ, mỗi lần nhìn lại mỗi lần mới tinh.”

“The blue water is clear. In the water of a thousand rivers, the moon appears.

The mountain cliff is beautiful. Every time you look at it, it is brand new.”

I would like to say to Thay: “Dear respected Thay, I am very happy because every day I see our direction clearly and know where I am going. The gratitude I have for my teacher, for the Patriarchs, for my spiritual family, for my parents, and for my blood family will never run dry. In 2024, we commemorate the two years of your passing; but right now, I know that you are roaming freely, and that you will still be forever in our hearts.”